One of the most explosive mixtures throughout history has always been that of politics and religion. Whichever way you approach it, you always come out burned and wrong.

If you look at it from the point of view of religion, you do not understand the maneuvers lacking in supernatural sense, moved simply by the pettiest envy. If you look at it from the angle of politics, you are always amazed at how short Machiavelli came up short, thinking of government without limits or scruples.

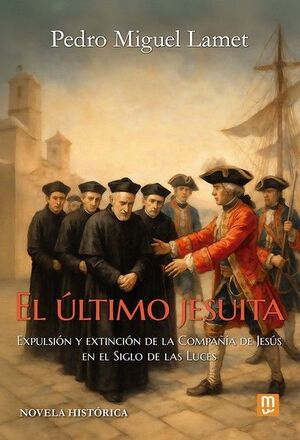

The Jesuit Pedro Miguel Lamet (Cádiz 1941), one of the best writers in the Spanish language, has just delivered a literary jewel of historical plot about the expulsion of the Jesuits from various European countries until their suppression by Pope Clement XIV, on July 21, 1773.

As always, the strength of Lamet's novels lies in how extensively documented they are so that the gentlemen's agreement of the historical novel is fulfilled: everything that is narrated could have happened and surely did happen, albeit with some name or circumstance changed.

The Intrigue of the Apostolic Brief and European Diplomacy

The advantage of the historical novel in Lamet's hands is that it makes history much more attractive because it enhances the intelligent interpretation of historical data by the work and grace of a fine observer.

For example, it is enough to read the masterful scene in which the future Count of Floridablanca teaches Mateo the Apostolic Brief “Dominus ac Redemptor” in which the Holy Father, as a result of the diplomatic pressure of the kings of Spain, France, Portugal and Austria to suppress the Society for the sake of the unity of the Church, at that moment of the maximum triumph of Charles III, of Caesaropapism, realizes that this suppression is “personal”, it is falsely torn, temporary, inadequate: “a brief is revoked with another brief” (21), it does not have the force of the juridical reason of the suppression by a pontifical bull that has the backing of the curia and the bishops (25).

Indeed, Pope Clement XIV had won the game, he had removed the diplomatic pressure, retained the maximum spiritual power, got rid of his enemies and succeeded in safeguarding the Society of Jesus which, with a simple Brief, would return to existence purified and splendid a few years later with the unconditional support of the entire universal Church.

The historical setting of the Jesuits

Pedro Miguel Lamet has succeeded in explaining in an entertaining and simple way one of the most studied and commented historical enigmas of the last centuries, a demonstration that the Society is of divine origin and will remain until the end of time. The question has always been twofold and until now we had partial answers.

First, Lamet gives us the historical setting, the successive attacks, meticulously designed by a force that has always been attributed to Freemasonry but which Lamet simply dismantles.

Lamet solves the first part of the enigma by noting down the slanders and defamations to which they were subjected and which are passed from hand to hand, we will see in short how the atmosphere can deteriorate, create a climate of opinion, of slander accelerated by the simplest envy (121-122).

Jesuit slander, conflicts and missions

Let us simply note the explanations expressed by the various Jesuits who are presented throughout this magnificent historical novel. In the first place, the mixture of religion and politics of the “Reductions of Paraguay”. In order to understand this issue, it is necessary to go back to the various disputes over the limits of the influence of Spain and Portugal in America.

The “Reductions”, commissioned by a mission area in a territory under Spanish influence, would pass to Portugal and the Portuguese government decided to put an end to the utopia of Thomas More that the Jesuits had set in motion and would hand over the missions to Brazil, which would want nothing to do with them and would destroy one of the most interesting proposals for the pedagogy of civilization in history. Therefore, the Jesuits would be free from the authorities: a political group (38).

Other calumnies against the Jesuits are more simplistic, such as the attack that they preached a relaxed morality and therefore were to blame for the spiritual and moral deterioration of the European courts that had Jesuit chaplains. It is not to understand the probabilism that affirms that “doubtful law does not bind” (82).

Another commonplace was to attack the famous Jesuit missionary Ricci and affirm that in order to ingratiate himself with the Chinese authorities he would have changed the message of Jesus Christ for a mixture of Christian revelation and Chinese cultural traditions. History has shown that the Catholic Church in China is faithful to the doctrine of Jesus Christ (101).

Let alone blaming them for having divided the Church because in France all those who did not think like them in moral matters were called Jansenists and heretics. They were self-referential and in their books they only quoted Jesuits. It is very interesting to study Pascal's “Letters to the Provincial” to see that if Pascal had succeeded we would all be scrupulous now. His criticisms are simply arithmetic as opposed to prudence.

The motives of Charles III and the reform of the Church

Finally, we must go to the heart of the matter, as Lamet does: the great unanswered question. Indeed, Charles III will say that the real reasons for the expulsion and suppression were left to his real conscience.

What could these “real” motives be? Lamet answers masterfully by explaining, without explaining it explicitly, that Charles III wished to carry out the reform of the Church in the world, as Henry Kamen has explained, with his hands free and he was hindered by the Holy See and the Society.

Indeed, Charles III and his successors imposed the Cortes of Cadiz, liberalism, the suppression of religious orders, “the religious question”, the disentailment of the “dead hands”, the quotas of seminarians and novitiates according to the needs of the dioceses, that is, the Church subjected to the State, dedicating itself to explaining the “constitution“ to the people and asking permission from the mayor of the town if it was going to leave on a trip. That is to say: the 19th century.

Thank goodness for democracy, religious freedom, the respectful separation of Church and State, the social doctrine of the Church, the Second Vatican Council and the universal call to holiness.

The last Jesuit. Expulsion and extinction of the Society of Jesus in the Age of Enlightenment.