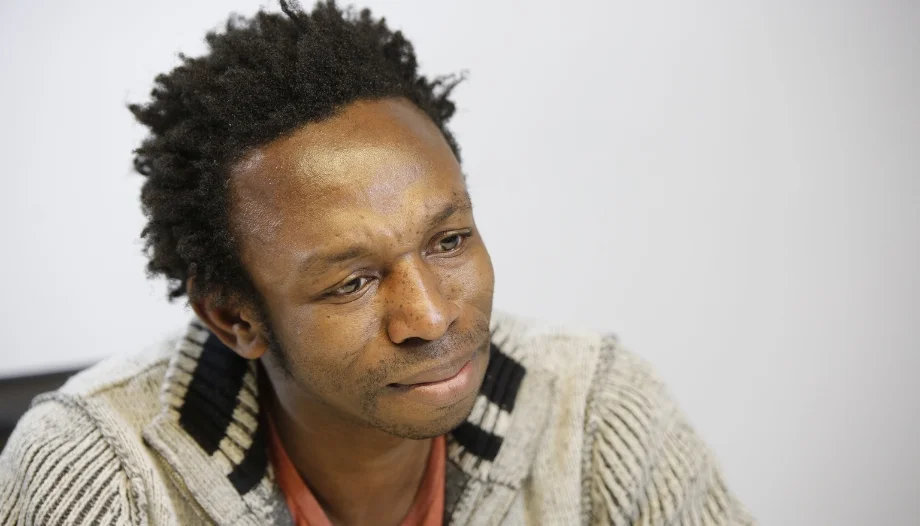

Ousman Umar did not leave his village thinking he was going to Spain. “I was going to paradise,” he repeats. He was born in a small rural community in northern Ghana, surrounded by jungle, with no access to formal education and less than 100 inhabitants. There, information was passed down from generation to generation and the world was explained through stories. His began marked by loss: his mother died during childbirth and, according to the beliefs of his tribe, that made him an “evil” child, the bearer of a spirit that was too powerful. In many cases, that stigma meant death. Ousman survived because his father was the village shaman and no one dared touch the healer's son.

Since he was a child, he had an inexhaustible curiosity and great ability to build things with his hands. When he was only nine years old, he was sent to the city to learn sheet metal work and welding. He built cars and trucks without ever having seen a real one. He didn't know then that that first trip would be the beginning of a journey that would take him halfway across the African continent and across the sea by boat.

Towards «paradise».»

In the port of Ghana he discovered ships, cranes and goods from the West. He wondered why the “whites” could create all that and they could not. That question, coupled with a lack of information and opportunities, pushed him into the hands of a network of human traffickers. Hiding in trucks, he crossed borders at night until he reached Niger.

«Then we went up to Gades and there they offered to take us in Land Rovers to cross the Sahara desert. After six hours of travel they abandoned us in the middle of the desert and never came back, so we had to cross the desert on foot».

Ousman says that there were 46 of them when they started walking and only 6 made it to Libya alive, «not counting the corpses we found along the way». He describes the 21-day journey as a living hell. Without food and drink, Ousman says that «whoever could pee was lucky.

At the age of 13, he arrived in Libya, with no language, no family and no protection. There he spent four years «practically enslaved» until he gathered the necessary money ($1800) to pay the traffickers. He was promised that in 45 minutes he would reach “paradise”. The reality was a new three-month ordeal through Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Mauritania and Western Sahara.

«Between Mauritania and Western Sahara they hid us in the dunes, and there they gave us wood and we made two small boats. I say »pateras" for the sake of argument, but we were really making a coffin".

«I took two boats. In the first attempt between 150 and 180 people drowned. Mine went back to land. We were in the desert for almost a month and a half until they brought us more wood so we could make a second attempt. We set out on two boats again and in the middle of the sea one of them sank. Mine, after two and a half days, reached Fuerteventura».

Indifference

Once in Spain, the CIE (Centro de Internamiento de Extranjeros) confirmed that he was a minor. In Malaga he was asked where in Spain he wanted to go. He only knew one word: «Barça». So he arrived in Barcelona on February 24, 2005, alone, with no language and no one waiting for him. He slept on the street for almost a month. “The worst thing was not the hunger, it was the indifference,” he recalls. The feeling of not existing for anyone.

«It was terrible to live on the street. In the desert, at least, there were five people surviving with me with whom just looking at their eyes, their looks, gave me back my humanity. But on the street no one looks you in the face. When I tried to ask for a glass of water, people would hide their bags, thinking that you were going to rob them».

Ousman's angel: Montse

Ousman's life changed when one day what he calls his «guardian angel» appeared: «I had just got up on Navas de Tolosa street, a very short street, and a lady who lived half an hour from Barceloana was there that morning. Suddenly, something told me ‘get up and talk to that lady who is going to save you’. I got up enthusiastically and followed her as if I knew her from somewhere. When she noticed, she turned around, and instead of getting scared, she grabbed my hand. I had been on the street for more than a month, with the same clothes, dirty... And she took my hand!».

Montse, who is now his foster mother, took him into her home that day. She fed him dinner and tucked him in «like a 5-year-old», kissed him and left the room. Ousman says that despite going from the cold of the street to a comforting home, it was the worst night of his life. «It was the first time I didn't have to fight, it was all over. But I kept asking myself ‘what was the need to suffer so much, what did I do wrong, why did my best friend die, why didn't he come alive, why me?'» Ousman thus came to the conclusion that the question should not be «why» but «what for».

Today Ousman is clear about his «what for» and that is to give a voice to those who did not reach «paradise» alive, and to those who continue to die every day in that infernal journey. «And to work to prevent others from suffering what I have suffered» he adds. This is how the NGO he founded was born: Nasco Feeding Minds. «I understood that all of us who came, came for lack of training, information and an opportunity. It is necessary to generate an opportunity there.

Nasco Feeding Minds

With his own savings, and with help from friends, Ousman went to Ghana and bought 42 computers, hired two teachers and opened the first computer school at St. Augustine June High School. «Today, after 13 years, we have almost 17 computer centers used by more than 58 schools and, this year alone, we reached more than 6,000 students.».

In 2021, when the first graduating class graduated, they created a small outsourcing and programming social enterprise. Now 23 people work at Nascutec, their social enterprise in Ghana, and 13 of them already work for Banco Santander in Spain, «with a decent salary, without the need to get on a boat or jump over any fences.».

«We believe this is the only truly transformative aid: not just giving food for a day, but feeding the mind. Because education allows them to build their own future with dignity,» Ousman says with conviction.

«Africa does not need charity, but prosperity.»

Ousman argues that aid to Africa should be based on respect, dignity and equality, not charity or paternalism. He criticizes the idea of “going to save” anyone or imposing solutions from outside without knowing the local reality. For him, before acting, we must listen, ask questions and treat people as equals, understanding that they know better than anyone else what they need.

He also questions welfare volunteering focused on handing out clothes or food or taking photos of himself helping children. He believes that this type of help only solves one-time emergencies and, in the long term, generates dependency and feeds the ego of the helper rather than the real well-being of the recipient. Instead of replacing families, she proposes giving resources and opportunities to mothers, young people and communities so that they themselves can take care of their own.

Its commitment is clear: “feeding minds”. In other words, investing in education, training and employment so that people can create their own prosperity with autonomy. For Ousman, teaching, training and generating decent work is the only way to bring about real and lasting change, because it is not a question of feeding one day, but of providing tools for life.

What to do with «our poor»?

Ousman suffered firsthand the indifference of passersby in Barcelona. «Many passed by and threw things at me. No one saw me, rather they pretended not to see me. A trash garbage can was worth more than me.»

When asked what can be done for «our poor» his answer is clear: «even if it is only five minutes of your time. What does he need? Don't draw your own conclusions about what you think he needs. Listen to him. And if you don't have time to listen to him, give him a smile: it's free! Give him back his humanity. What I missed the most was humanity, more than food».