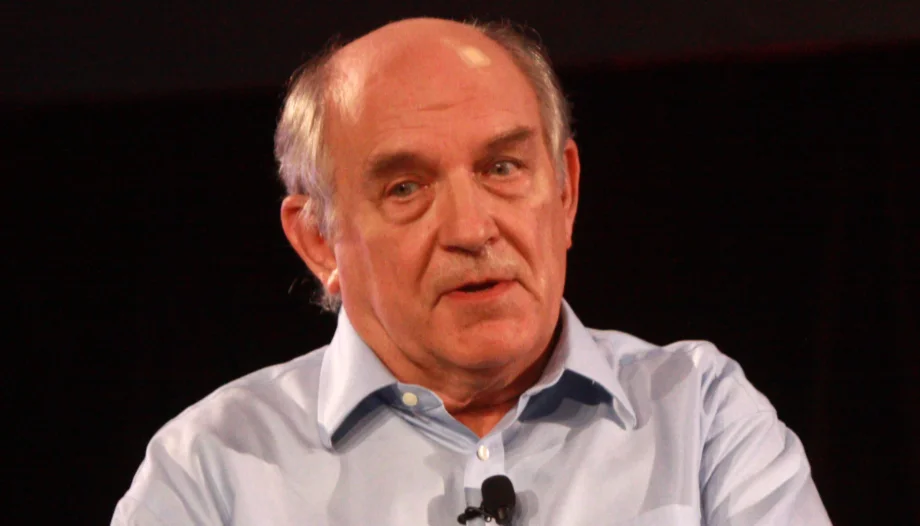

The influential political scientist and writer Charles Murray, known for his libertarian stance and his views on American social inequality, has just published his new book, "The American Way of the World. Taking Religion Seriously (Taking religion seriously). Murray, a Harvard graduate with a Ph.D. from MIT, embarks on an intellectual and personal journey that takes him from enlightened agnosticism to a sincere openness to the possibility of God.

The author, famous for his rational analysis and polemical theses on Western culture, admits that for decades he considered himself a convinced secularist, but that a series of "nudges" - as he calls them - led him to question his materialistic certainties.

He explains that he has had a good enough life not to have been forced to believe in a God that would give meaning to his suffering: "I have lived my life without ever reaching the depths of despair", he explains in an article published in The free Press and from whose content we extract the quotes in this text.

The confession, intimate and honest, sets the tone of a book that mixes philosophy, science, biography and spirituality. Murray acknowledges that his training protected him from deep suffering - and also, paradoxically, from the yearning for the transcendent.

From Thailand to metaphysical thinking

The story goes back to his youthful years in the Peace Corps in Thailand during the 1960s. There he practiced transcendental meditation, in search of an enlightenment he never achieved. "I tried, but it didn't work. On the rare occasions when I approached a meditative state, I could feel my own resistance."

That failure planted in him a persistent intuition: that people have different capacities for spiritual perception, just as some are more sensitive to music or art. Decades later, as he watched his wife Catherine delve into Quakerism, Murray thought she was "suffering from a perceptual deficit in spirituality."

Murray's wife was a pious Quaker and, he believed, did not believe out of self-deception, as atheists often think. That disarmed him: "She had an extraordinary intellect...and she was not self-deluded in any way. Through her example I came to accept that I was the one who had a problem."

The dismantling of its secular catechism

Murray devotes a central chapter to dismantling what he calls his "secular catechism," the series of three dogmas he had accepted without examination for decades:

- The concept of a personal God is at odds with everything science has taught us.

- Humans are animals... When the brain stops, consciousness also stops.

- The great religious traditions are human inventions, products of the fear of death.

That set of convictions, he says, constituted his intellectual comfort zone, devoid of any deep reflection. Murray does not disavow science, but he reproaches modern thought for its lack of metaphysical curiosity.

The process of his doubts began with small nudges-casual reflections, outside questions, readings-that eventually undermined the structure of his skepticism. The question that changed everything: "Why is there something instead of nothing?" "Surely things don't exist without having been created. What created all this?".

Reflecting on these questions, he better understood the limits of reason. The idea that existence itself demands a cause led him to accept that there is a "Mystery with a capital M" at the origin of everything. "What Mystery really means is that the universe was created by an unknowable creative force...a concept that Aristotle referred to as the 'immobile motor. Murray confesses that, for the first time, that concept struck him as an intellectually acceptable description of God.

Deanthropomorphizing God

The next step in his spiritual evolution was to free himself from the human image of God. "Any God worthy of the name is at least as incomprehensible to a human being as I am to my dog."

The comparison serves to express the distance between the Creator and the creature. His dog perceives him partially, without understanding his essence; in the same way, the human being only grazes the divine mystery.

This process of "deanthropomorphization" freed him from the childish caricatures of the bearded and paternalistic God, allowing him a faith open to mystery.

A book that challenges non-believers

Taking Religion Seriously is not intended as a theological work, but as a cultural and personal reflection. Murray addresses himself especially to modern intellectuals, those for whom religion seemed a residue of the past. His message is clear: faith, properly understood, does not contradict reason; it completes it.

"In the 21st century, it's easy to stay entertained and distracted. And that, I think, explains a lot not only about me, but about the carefree secularism of our age."

Murray attempts to bridge the gap between the modern mind and openness to the supernatural. He acknowledges the persistent skepticism in our culture, but invites his readers to reconsider that the search for God is a legitimate task of human thought, not an irrational flight.

At a time when many wonder if the West is undergoing a "religious renaissance," Murray offers his personal answer: yes, but it must begin within every soul who - like him - dares to look into the void and discover that perhaps that void is in the form of God.