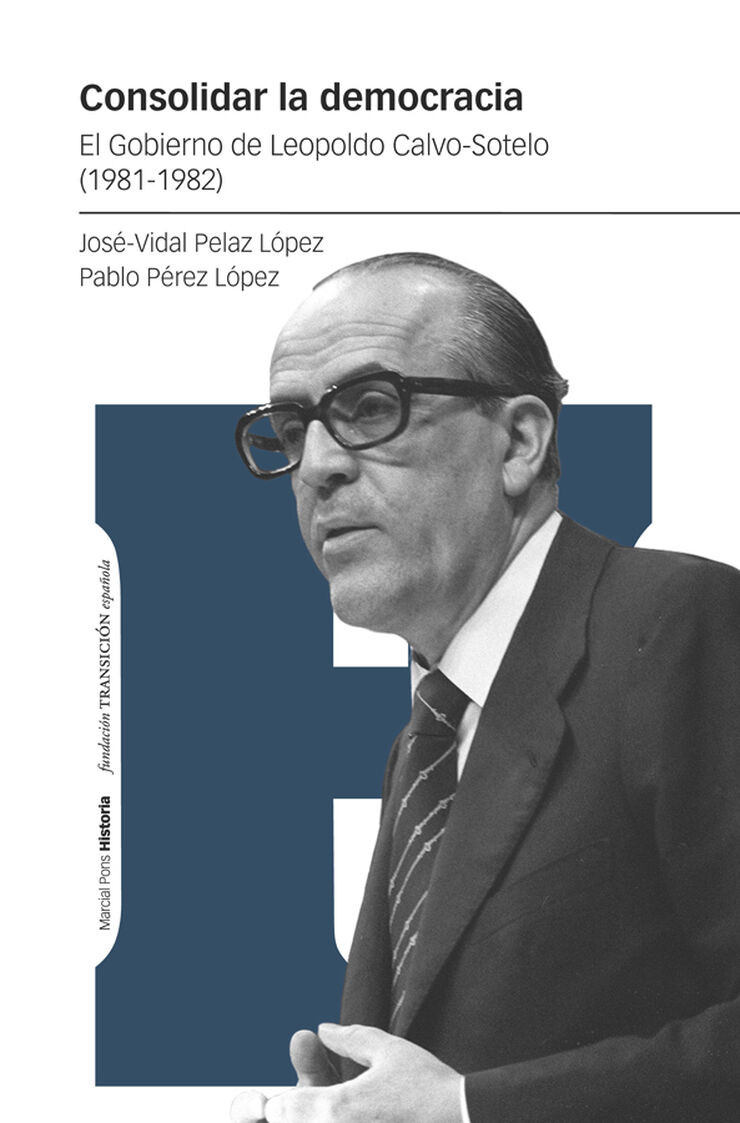

The Spanish "Transition" Foundation and Marcial Pons Editions have published this magnificent work about the work of the second democratic president of Spain after the constitution of 1976, Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo (1926-2008).

The work has been written by two young professors of contemporary history, José-Vidal Pelaz López of the University of Valladolid and Pablo Pérez López of the University of Navarra, both friends and colleagues at the University of Valladolid and specialists in this period of Spain's recent history. This team promises and announces new and interesting works on the history of Spain during the Transition since, as they point out, they have extensive archives of the personalities of the Transition.

A documented investigation

Likewise, it gathers with great intensity and very solid documentation, the first moment of real danger during the course of the Spanish political Transition that took place between 1981 and 1982, where three capital events took place in the incipient Spanish democracy.

Firstly, the departure of Adolfo Suárez from the government in 1981, the key man in the transition from dictatorship to democracy, since King Juan Carlos I handed over the government to him in 1976 with the task of installing democracy in Spain.

The second danger occurred in the middle of the investiture debate of Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo in 1981, the failed military coup of 23-F, with the profoundly democratic actions of King Juan Carlos I, the still president Adolfo Suarez and his vice-president General Gutierrez Mellado. This failure was, undoubtedly, the end of the interventions of the army in Spanish politics that had been so frequent in Spain in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Transition

Finally, after Calvo-Sotelo failed in his attempt to unite the ruling UCD party with the presidency of the government, it ended with the early elections of 1982 and the Socialist victory by absolute majority.

The first key to this transition was Calvo-Sotelo, who governed in a climate of democratic normality, with a magnificent government program, to end up ceding power to Felipe González, who would govern for fourteen endless years to culminate the transition, since alternation in the institutions is fundamental to measure true democratic maturity. That is to say, the real alternation of government and, for many years, it reflected the democratic normality that had ended up being installed.

It is interesting that the UCD parliamentary group broke up (p.130) because it housed within itself a real amalgam of political ideologies, from the social democracy of Fernández Ordoñez and Meilán Gil to some characters like Iñigo Cavero of the Christian democracy and Herrero de Miñón who would leave with Fraga: a political project always leaned to the right that had collaborated with Franco's regime, which would stagnate Spanish political life because it could not offer a plausible alternative to the Spanish people who wanted to be democrats and turn the page with respect to the previous dictatorship.

Socialists

Another of the keys highlighted in this interesting work would be the real and true collaboration of the socialists in the Spanish government during the period of Calvo Sotelo, which was perfectly compatible with the usual parliamentary squabbles. In fact, the development of the autonomous regions, the entry into NATO, the support against the very hard offensive of ETA that gave no truce to the government, keeping the army out of the area of influence in the executive (for which he could count on the support of the king) (p.149), fundamental and urgent economic measures. The book notes many cordial meetings between the two leaders who worked together.

Even in the critical moments of the UCD, Calvo-Sotelo had the proposal of a coalition government between the Socialists and the UCD, although in reality the coalition government was already suffering from it. Calvo-Sotelo in his skin before Fernández Ordoñez went to the socialists and Herrero de Miñón to Fraga (85). This can be seen in the balance of forces in the government crisis of January 15, 1982 (141).

Certainly, the search for the "legitimization of the democratic left" was a fact in those years, as it would be later when the Socialists governed with the unions, especially with the sister UGT (29).

The detailed explanation of the autonomist turn of the PSOE made by our authors is interesting, since from Suresnes where "-A Federal Republic of the nationalities that make up the Spanish State" was claimed to the Spain of the Autonomies reflected in the Constitution there are many important changes and not of mere political opportunism as the authors gather with abundant documentation (191, 192). To which they add: "Only the PSOE was willing to reach an agreement, perhaps because the socialists understood that the moment was approaching when they would have to face the responsibilities of government" (193). Also interesting are the intense relations with Jordi Pujol and Miquel Roca (206-207).

The economy

With respect to the economy during that short period of time, it should be remembered that it was the worst year in the countries around us, but on the other hand, the skill of Calvo-Sotelo and his ministers managed to ensure that "Spain grew between 1.5 and 2 percent, compared to an average contraction of 0.2 percent in the OECD economies. This had made it possible to improve the evolution of employment; unemployment had grown, but at a slower rate than in other years" (265).

It is interesting that there is no reference throughout the book and no chapter dedicated to Church-State relations. This indicates that the suggestions of the Bishops' Conference to encourage Christians in social concern and to live the social doctrine of the Church.

Consolidating democracy