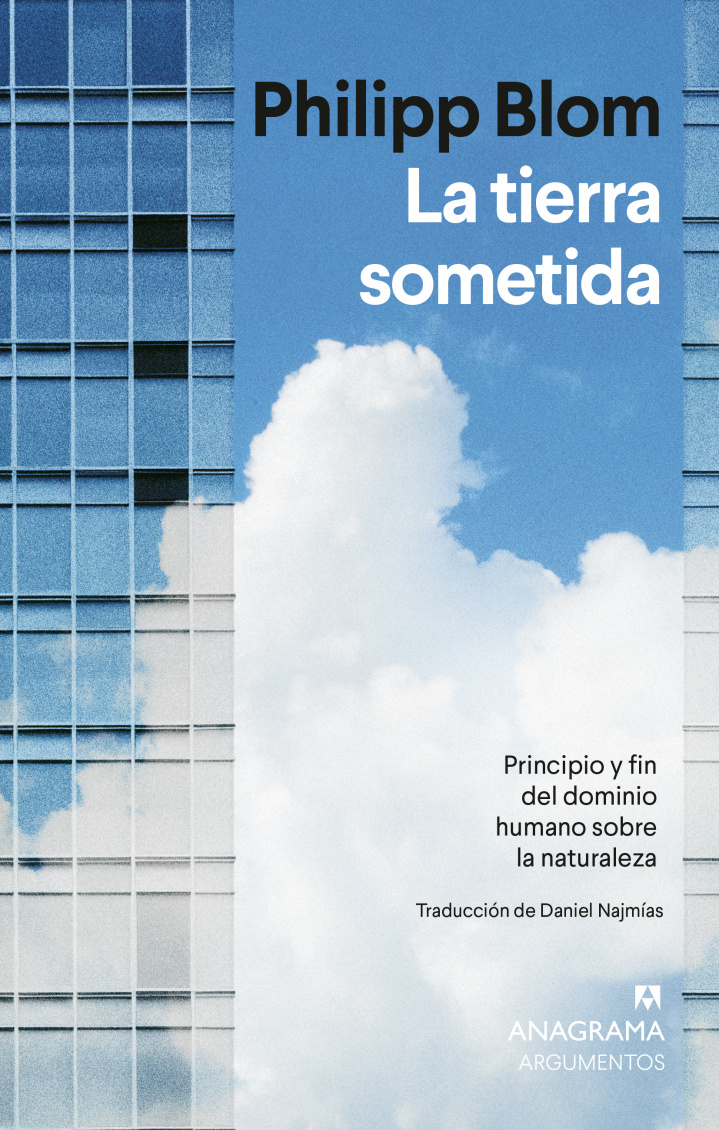

Man's relationship with the world has had different interpretations throughout history and, above all, today we have a clear feeling of having arrived late in the despotic domination of nature, as if it were beyond repair and we had caused an almost irremediable deterioration. It is within this framework that this extraordinary work by historian Philipp Blom, always intelligent and with ideas to contribute to the intellectual debate and to historical science, moves.

Of course, he will always speak from the history of ideas, with depth and rigor, in spite of being diverse and dispersed themes. Blom's visit to Sacred Scripture and classical antiquity is very important to prove the sin of idolatry of the Jewish people (p. 63) together with the command to “subdue the earth” (p. 93).

Reason at the service of the mastery of nature

Regarding St. Augustine and his famous contribution in the treatise “de bono matrimonii”, about concupiscence, Blom reminds us of its origin in Manichaeism and neo-Platonism, which would explain “the obsession with Greek systematics, the Platonic opposition to carnal pleasures and Manichaean paranoia” (p. 112).

Particularly interesting is Blom's study of one of the fathers of modern science, Francis Bacon (1561-1626), a contemporary of Montaigne (1533-1592), but much more incisive than him in subduing the earth with instrumental reason (p. 186). For example, in his “Novum Organum” he will tell us: “Man, servant and interpreter of nature, neither works nor understands except in proportion to his experimental and rational discoveries about the laws of that nature: outside of that, he knows nothing and can do nothing” (p. 187).

The parliamentary Bacon ended badly but the “jurist and political Bacon was a productive thinker in his conversations or in correspondence with other scholars” (p. 188). That is why Blom will assert: “Bacon's ambition went further: he not only wanted to be a servant of nature: he also aspired like Telesius, to master it by learning, to know it from the inside out” (p. 192).

Blom will end this short synthesis of Bacon's thought with a quotation from Descartes to close a chapter that began with the rationalist's view of the animal soul (p. 178): “Descartes recognized that his image of nature also rested on the opinion and interests of the masses, but in his books he defended it until he ran out of ink: only man alone has a soul; the rest of nature is composed of non-sentient automatons that are to serve man, with the help of reason, to carry out - by mastering it - his divine mission” (p. 193).

He then turned to Baruc Spinoza (1632-1677), an author so vilified in his time that he could hardly be mentioned in the intellectual debate because he was considered “subversive and scandalous” (p. 194), for he claimed that “God is matter and the laws of nature, and the world, in Spinoza's legendary formulation, is deus sive natura, God or nature, two interchangeable terms” (p. 196).

And more: “As an attentive reader of Montaigne and Bacon, of Telesius and Descartes, Spinoza knew the models of his predecessors and developed his argument with unsurpassed elegance, as if Montaigne had moved Descartes” pen. Nature is an infinitely complex system whose laws are circumvented and distorted through ignorance or greed“ (p. 198). Finally Spinoza was buried in the index of banned books, ”however, his work sank under the general movement towards the new gospel of scientific and rational domination of nature, engine of new prophets..."(p. 199).

The Enlightenment was never a school of thought with binding dogmas, apart from the emphasis on reason, a basic optimism and a certain elitist tendency which, however, already had very different faces“ (p. 208). In addition, various trends began to differentiate themselves: ”The rationalist and moderate enlightenment of Immanuel Kant or Voltaire, Thomas Hobbes or Leibniz was, for many of its opponents, an attack on the traditional order of the world, although in reality it also played the opposite role, because in a secular world it breathed new life into many central ideas of the Christian theological tradition“ (p. 209).

Blom then reminds us: “Most of the enlightened had received a Christian education and these ideas were so familiar to them and their societies that they seemed to them the only possible structure of thought. Although the Enlightenment authors attacked Christian dogmas, they also used arguments and conceptual images from the Christian tradition to rewrite them in their own way” (p. 211).

Logically, Philipp Blom had to dedicate a chapter to the Lisbon earthquake of November 1, 1755, which caused thousands of victims in that city and in others nearby and, in addition, the tsunami that took thousands more people and, above all, a broad and heated philosophical, scientific and theological debate about physical evil and moral evil (p. 219). The conclusion, for Blom, after exposing the Kantian, Voltairean or Herderian arguments is the following: “Lisbon became synonymous with the analytical weakness of rational religion. At least for the educated elite, the earthquake of 1755 was an intellectual tremor” (p. 223).

Moreover, he will add: “After all, both the aristocracy and the Church derived their legitimacy from a divine mandate and the grace of God (even the rich Calvinists had learned to consider their prosperity as proof of God's favor, which at the same time allowed them not to feel responsible for the poor). Therefore, any reasoning that questioned the divine order and removed the authority of knowledge and morality from the throne and the Church was in itself a revolutionary act” (p. 224).

Having arrived at the substance of the Enlightenment Blom will tell us: “On the one hand Kant drove his contemporaries to despair insofar as his philosophy affirmed that with the sensory experience of the essence of the world it was impossible ever to perceive anything and therefore nothing either of an expected spiritual truth, i.e. of God, but, on the other hand, like Descartes with his res cogitans, created a space that made room for mystery and the Creator, a place that would never be touched by science” (p. 226).

The subdued land