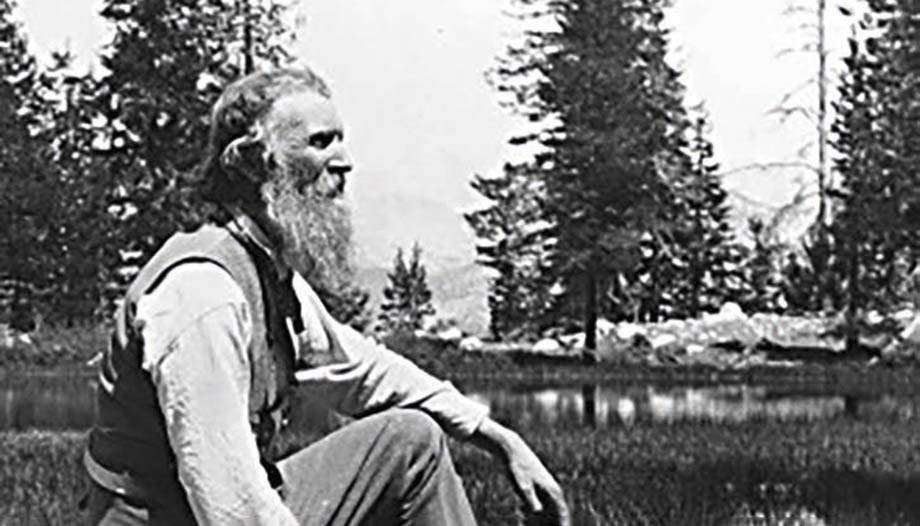

Who is that bearded man wearing a wide-brimmed hat and gazing intently alongside the President of the United States at the abyss of Yosemite? He is neither a politician nor a military man, but a naturalist who made contact with nature his life's mission and who knew how to convince a president of the need to protect the wilderness.

John Muir, with his gaunt figure and biblical prophet's beard, was not only accompanying Theodore Roosevelt on that famous 1903 excursion: he was, in fact, convincing the president that the wilderness should be protected for future generations. That photograph is now the symbol of a seminal moment: when the contemplation of nature became conservation policy.

Origins

Muir had come a long way to reach that summit. He was born in Dunbar, Scotland, in 1838, and emigrated to Wisconsin, in the United States, at the age of eleven. His life on his family's farm was marked by the hard work imposed by his father. Those hours of intense effort contrasted with moments of freedom, when he would walk with his brother through the meadows and stop to watch a bird or a flower. That childhood experience, a mixture of severity and wonder, nurtured a sensitivity that would never leave him.

Contact with nature

In his youth, he stood out as an inventor and studied chemistry, botany, and geology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. A serious accident in 1867 left him almost blind, but his recovery marked the beginning of a new life: he set out on a journey on foot of more than 1,800 kilometers to the Gulf of Mexico, and from there he reached California, where he began to explore Yosemite. There he found what he would call his true home. “Going to the mountains is like coming home.”, I would write in My first summer in the mountains (1911).

His life became a constant pilgrimage. He discovered the glaciers of the Sierra Nevada, traveled to Alaska and named the Muir Glacier, researched the ecology of giant sequoias, and traveled throughout South America, Africa, and Australia. But he always returned to Yosemite, where the experience of the wild revealed itself to him as a sacred mystery.

At The mountains of California (1894) wrote: “When we try to distinguish something on its own, we discover that it is connected to everything else in the universe. On every walk in nature, you receive much more than you were looking for.”. That conviction of interconnectedness led him to assert that wilderness was not a luxury, but a vital necessity. “Thousands of tired, nervous, overly civilized people are beginning to discover that wildness is a necessity.”he wrote in Our National Parks (1901).

For Muir, that need was also an inner calling. In a letter to his friend Jeanne Carr, he simply expressed his destiny: “The mountains are calling, and I must go.” (La vida y las cartas de John Muir, 1924). But he did not want to keep this revelation to himself. In his diaries he states: “Everyone needs beauty as well as bread, places to play and pray, where nature can heal and give strength to both body and soul.” (John of the Mountains, 1938).

That pedagogical vocation turned into political action. In 1892, he founded the Sierra Club, which is still active today, and devoted his energies to defending Yosemite and the national parks. He understood nature as a school and teacher, capable of teaching more clearly than books: “The clearest path to the universe is through a wild forest.” (Un viaje de mil millas hacia el golfo, 1916).

From nature to God

For John Muir, the wild forest speaks to us of God. Muir had abandoned his family's Calvinism, which tended to view God as totally alien to the world. Although he had little connection with the Catholic tradition, Muir seems to have sensed—according to scholar Tim Flinders—the divine presence that animates the natural world., “who inhabits the universe and fills it with light and harmony” (John Muir: Spiritual Writings, p. 24). Through his work, his writings, and his life, Muir taught that nature can lead us to discover and admire its Creator.

His thinking combined the spiritual, the scientific, and the political: spiritual, because he saw the sacred in the wild; scientific, because he rigorously studied geology and botany; political, because he knew how to influence laws and presidents. He believed that nature should be preserved. “for the benefit and enjoyment of all the people”, as a common good of humanity.

The 1903 photograph in Yosemite sums up that entire journey. On one side, Roosevelt, embodying the power of the state; on the other, Muir, with his fiery gaze and hermit-like demeanor, embodying the voice of the mountain. Between them, the immense landscape of Yosemite, witness to a pact in favor of conservation. Perhaps that is why, when we look at the image again, we understand that it portrays not only a president and a naturalist, but humanity in dialogue with the wild. Roosevelt represents political power; Muir, spiritual power. And between them opens the horizon of nature, which seems to remind us that true greatness lies not in domination, but in preservation. There, in the silence of Yosemite, Muir's call still echoes: the mountains continue to call us, and we still have time to respond.