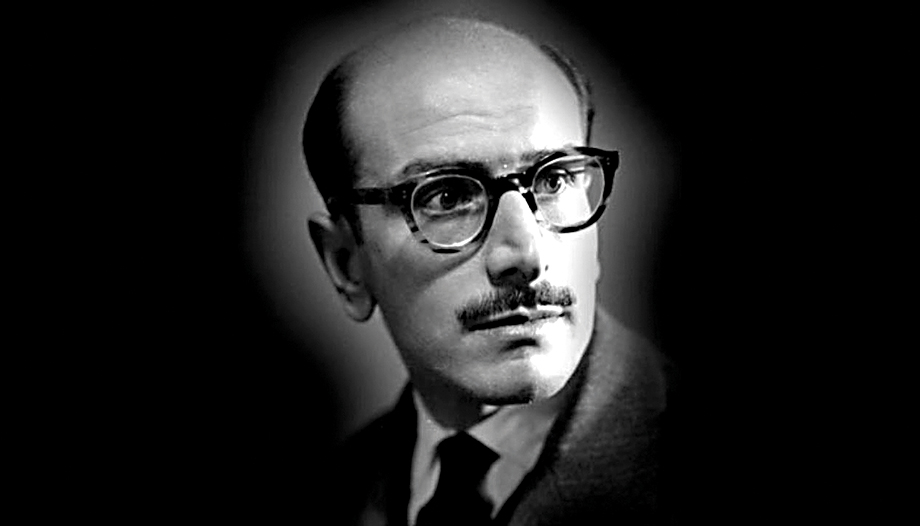

It was the poet and critic José Luis Cano who was confident that the publication of the Complete poems (1959) by Vicente Gaos would finally consolidate the place it deserved within the canon of 20th century Spanish poetry. However, time did not confirm that expectation. In spite of its depth and its indisputable literary value, his work remains on the fringes of the usual readings among poetry aficionados.

Religiosity and sensitivity

With profoundly religious roots - Gaos himself said so: “I consider myself a religious poet and much of my poetry is religious poetry”-., his production is inscribed, like that of so many authors of the first post-war period, in a context in which Spain officially recognized itself as Catholic. However, although he shared that framework, his voice differs from the dominant rhetoric, articulating an internalized, agonizing and, at times, heartbreaking religiosity.

From Angel of my night (1943) up to his posthumous collection of poems Last Thule, developed a poetry of remarkable vital breath. And although critics have rightly emphasized his sonnet mastery, this formal virtuosity was never reduced to a mere technical exercise, but was the precise instrument with which he explored the metaphysical restlessness, the search for meaning and the ambivalence of a faith that, far from being reassuring, is configured as an inner struggle.

Active presences and moral conflict

It is not surprising, then, that critics have pointed out the influence of Miguel de Unamuno, at least in his early works. The affinity is evident: both share the tension between the thirst for eternity and the certainty of death, as well as an inclination to doubt and radical questioning, a filiation that, however, only explains a part of the poet's spiritual framework.

What truly defines him is the constant confrontation of evil and temptation, presented not as abstractions, but as personified presences that burst into the consciousness of the poetic subject. Figures like Luzbel possess voice, gesture and capacity for action; they burst in as an “other” that threatens, seduces or hurts, transforming the intimate conflict into a scenario of permanent tension.

In this imaginary, two sonnets are particularly relevant: Sima and cima y My demon. In the first, the poetic “I" acknowledges his sinking into impurity -figured in a demonic abyss- while retaining an aspiration to the light. In the second, a confessional tone dominates: the poetic character evokes the temptation and the threat of spiritual slavery before underlining the divine mercy that reintegrates him into the "divine".“orderly sky".

However, the poetic work of Vicente Gaos is not limited to this moral problematic. It also integrates a persistent reflection on Death and Nothingness, conceived as a horizon of absolute annihilation. This is the case in the poem No one responds, where the perplexity of those who search for light in an inaccessible sky is expressed and where silence becomes a symbol of existential loneliness.

Even more shocking is, if that is possible, the poem The Nothingness, in which it cries out: Oh, save me, Lord, give me death, / Threaten me no more with another life (...) /...Oh God, give me your Nothingness, / Anchor me in your darkest night / In your lightless, starless night.”This fragment reveals the extreme dimension of his rebellion: the plea for total annihilation which, paradoxically, he addresses to God himself as the ultimate addressee.

The poem Error proofing

Within this lyrical universe, one of his most revealing texts is, in my opinion, the sonnet Error proofing. In fourteen verses, Gaos draws a path that leads from doubt to reconciliation, and in which he recalls having felt “...".“hunger, thirst and cold”without realizing that, even then, he was being held by the hand of God. This paradox - the false sense of abandonment that, in reality, prepares the access to grace - is the core of the poem.

Its architecture reinforces this process: first, the erroneous perception of distance; then, the irruption of Christ showing his wounds, like the Apostle Thomas, a sign of a faith born from unbelief; and finally, thanksgiving, where the relationship with God is transformed and the Lord becomes a Friend. Thus, the text unfolds a complete itinerary that summarizes the poetics of the author: tension between doubt and faith, suffering and hope, fall and redemption. Hence Error proofing can be fairly read as a synthesis of the lyrical world of Vicente Gaos.

That is why it is not difficult to return to the statement with which José Luis Cano opened his hopes in 1959. If time has not confirmed -at least in terms of popularity or canonical presence- that recognition he considered fair, it can be said that the careful reading of poems like this one demonstrates the profound validity of his intuition.

Perhaps today, more than ever, it is evident that Cano was not wrong: Vicente Gaos continues to await the place that his work -because of its density, intensity and expressive purity- claims in 20th century Spanish poetry. That depth and contradiction that run through his writing undoubtedly place him among the most lively and unrelenting voices of his generation -an “uprooted” generation that, in spite of everything, never lost its yearning for transcendence- and explain, at the same time, why his figure continues to challenge the contemporary reader with a force that the passage of time has not been able to attenuate.

Errors - From A lot of shadows (1972)

When I imagined you closer,

How far I was from You, my Lord.

When I was hungry and thirsty and cold

and distance from You, You of Your hand

you had me, Lord. That is your arcane

mystery. And I, my ungodly thought,

I didn't even believe in myself. Free will?

A Midsummer Night's Dream!

But suddenly You arose, solemn,

showing me the sores, as you did

with doubting Thomas, with me.

And I thanked you for saving me unscathed

from so much blindness in which you have sunk me

to rise up at the end, Lord, my Friend.