On December 19, the Catholic Church commemorates Saint Eve, the first woman according to Genesis. For many believers, this fact is surprising: Eve, usually associated with the story of original sin, is venerated as a saint.

Christian tradition views her in the light of redemption: Eve is not defined by the Fall, but by God's plan of salvation, culminating in Christ, the new Adam. Her memory appears in ancient martyrologies and in Eastern and Western liturgical traditions from the early centuries of Christianity.

The figure of Eva has developed around, outside the biblical canon and outside Catholic doctrine, a parallel tradition that has exerted a notable cultural and artistic influence: that of Lilith.

Origins of Lilith

Its roots lie in myths from the ancient Near East (Mesopotamia) and in later Jewish interpretations that attempted to harmonize the two accounts of creation in Genesis. This tradition took shape especially in medieval texts, where Lilith is presented as the first woman, created before Eve and separated from Adam after refusing to submit to him.

Over time, her figure became associated with the demonic, but also with rebellion and female autonomy, which explains her persistence in literature, art, and symbolic thought.

It should be emphasized, however, that this interpretation is not part of the tradition, teaching, or theology of the Catholic Church, and therefore does not in any way constitute a matter of faith.. Catholic doctrine recognizes only the biblical account of Eve's creation as presented in Genesis.

Even so, the tradition of Lilith is culturally relevant, as it has had a significant influence on numerous artistic, literary, and symbolic representations over the centuries, and allows for a better understanding of certain imaginaries that dialogue—albeit from the outside—with the great biblical narratives.

Lilith as the “first Eve”

The idea that Lilith was the first woman emerged later, when Jewish interpreters noticed the apparent contradiction between the two accounts of creation in Genesis: one where man and woman appear to be created simultaneously, and another where Eve is created from Adam's rib.

According to this tradition, Lilith did not have a harmonious relationship with Adam. After the conflict, God granted her the freedom to leave him, and she went to live with demons in desert regions, traditionally located near the Dead Sea. From then on, later Jewish literature describes her as an evil female spirit, associated with the night, seduction, and destruction.

In this context, some accounts identify Lilith as Eve's tempter, the figure who, driven by jealousy, incites the new woman to eat the forbidden fruit. In this way, the serpent of Paradise acquires feminine and demonic traits.

In modern times, however, writers, artists, and feminist movements have reinterpreted the myth, presenting Lilith as a symbol of female independence and resistance to the patriarchal order.

Outside the religious sphere, Lilith has been adopted by various contemporary cultural movements. Some hard rock and metal bands have used her name as a symbol of rebellion, power, and transgression, interpreting her as a figure who embodies strength in the face of the established order.

A character absent from the Bible

The Catholic Bible does not mention Lilith as a character in the story of Paradise.. However, in some ancient translations and Hebrew commentaries, it appears associated with terms such as owl, symbols linked to night, darkness, concealment, and sinister things. In the Semitic world, these names evoke nocturnal, twisted beings linked to evil deeds.

Rabbis and Talmud scholars developed the figure of Lilith based on a detailed reading of Genesis. In Genesis 1:27, it appears that God created man and woman simultaneously (“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them.”).

In Genesis 2:22, Adam appears alone and Eve is created from his rib (“And the Lord God formed a woman from the rib he had taken from Adam, and presented her to Adam.”). To explain this difference, some Jewish commentators argued that the woman created alongside Adam was Lilith, while Eve was a later creation.

Lilith in art: from the Prado to the Sistine Chapel

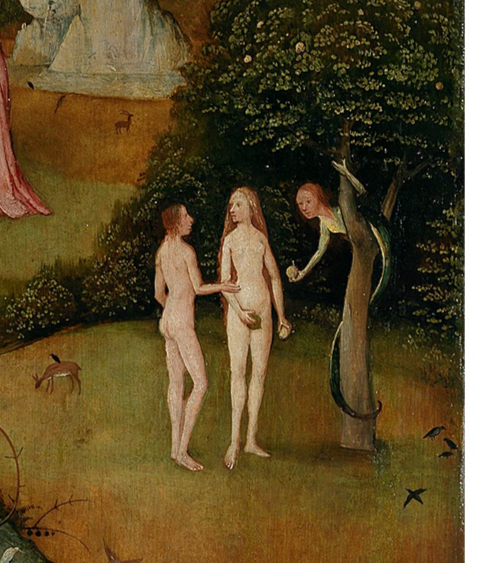

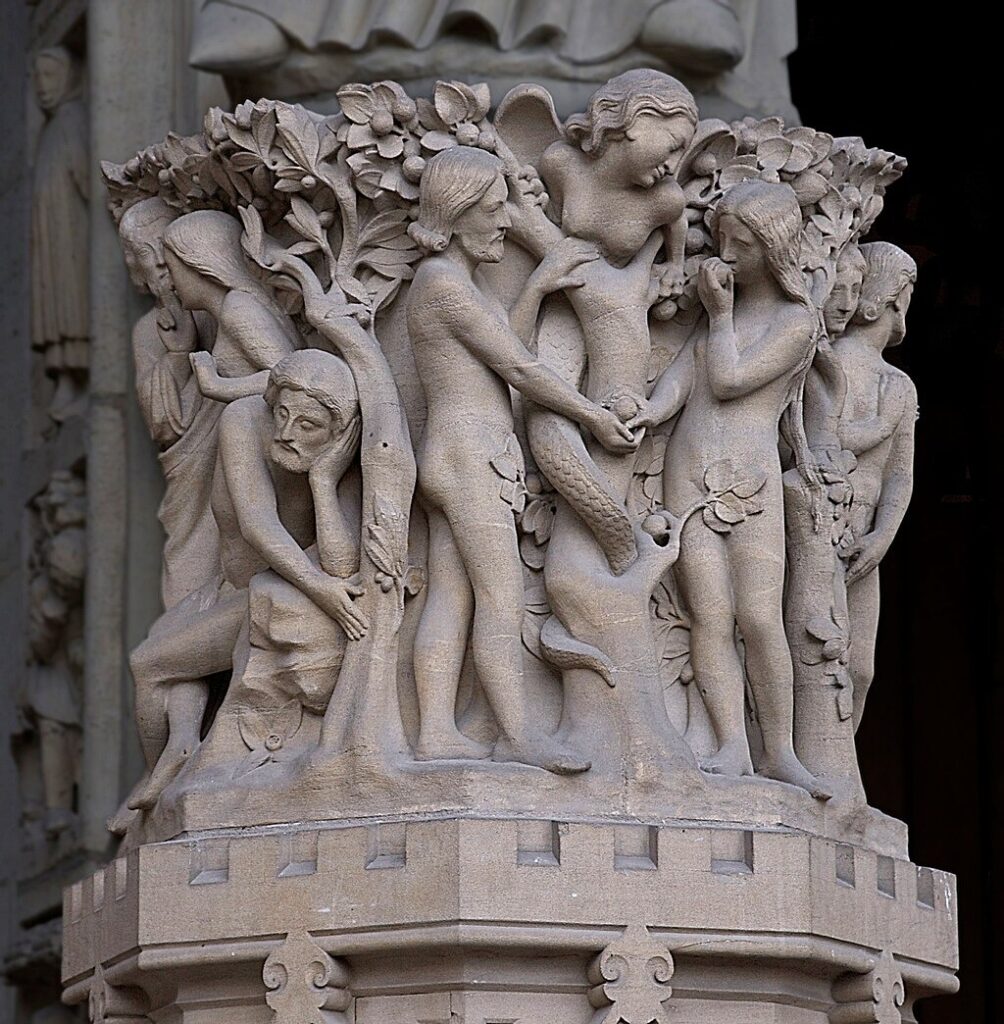

This tradition has left a particularly visible mark on art history. Several artists of the Renaissance and late Middle Ages depicted the temptation in Paradise with a serpent with feminine features, reflecting these Hebrew interpretations. It is usually depicted in the form of an owl, or as a woman or a serpent with female breasts.

At the Prado Museum, some of Bosch's works are particularly eloquent. In The Garden of Earthly Delights, An owl appears watching from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, like a dark and watchful presence.

In the Triptych of the Hay Wagon, also by Bosch, the demon tempting from the tree takes on a form clearly associated with this female figure.

Something similar occurs in the Sistine Chapel, where Michelangelo painted the scene of the original sin with a serpent with a female torso, an iconography that does not come from the biblical text, but from extra-biblical traditions known in humanist and Hebrew circles during the Renaissance.

In the Vienna Diptych Hugo van der Goes did not paint a conventional serpent, but rather a hybrid creature that fits perfectly with the figure of Lilith.

In the relief of the The Temptation of Adam and Eve, Located in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, the serpent also appears with the torso and face of a woman, coiled around the Tree of Knowledge.

Adam and Eve, by Raphael in the Vatican Museums, follows Michelangelo's tradition: it shows the serpent-woman with a face almost identical to that of Eve.

The exact reason why so many Catholic artists adopted the figure of Lilith—a character from Jewish tradition—to represent the fall in Eden is unknown. The answer seems to lie in the humanist circles of the time, where painters such as Raphael or Michelangelo may have included these features under the direct influence of a rabbi friend.

During a time of searching for original sources, the myth of ‘Adam's first wife’ filtered down to Christian painters, transforming the serpent into that reptilian woman we see today in the Vatican or Notre Dame.

If you are interested in these interpretations of Lilith, rabbis, and snakes with women's faces, you will surely enjoy reading the two volumes of the Bible for Dummies published by María Vallejo-Nágera by Palabra. They are full of interesting and very entertaining stories.

Bible for Dummies. Volume I