Let's start by remembering that the literary genre historical novel has gained an unusual space in our bookstores as can be seen in any of the most important ones, where the space dedicated to this subject has multiplied and where successful authors have grown enormously.

Logically, the incorporation of good historians and cultured and well-documented writers has contributed to this. Herein lies the success of the historical novel: to be faithful to the historical facts and, above all, to capture the mentality of the period in which it is set. Indeed, the reader is perfectly aware of whether the events being narrated correspond to the period: that is to say, that perhaps it did not happen exactly that way, but it could perfectly well have happened.

Precisely, when the pact between the writer and the reader is broken and the characters are placed in the current mentality or in another imaginary one, perhaps some copies can be sold among inexperienced readers, but, immediately the word of falsehood spreads and the works of that author will be in dead end, for lack of historical rigor and documentation: nobody likes to be deceived and even more in this time where there are more and more people with studies and knowledge of the cause.

In this sense, our authors who are not historians should try to read good treatises on history and realistic novelists of the period in which they are working, because in this way they will be formed and will incorporate the results of recent research.

Now we wish to deal with a recent historical novel, in order to apply what we have been discussing. In the case of the Inquisition, especially the Spanish Inquisition, it has experienced a remarkable boom from 1975 to the present day. It is enough to know that, in the first ten years of Franco's death, when censorship disappeared, more works were published on the Inquisitorial tribunal in Spain than in all of history. Both with works of serious research and dissemination.

A real case before the Inquisition

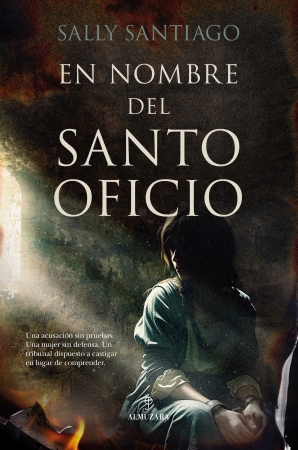

Specifically, let us comment on the recent work of Sally Santiago (Madrid 1966), an author of historical novels, a specialist in micro-stories who has embarked on writing a short novel set in the Spanish Inquisition in the seventeenth century.

Indeed, the author situates the work well, has read some popular works and has approached a cause still little studied, hence she points out on the back cover, to attract readers, that it is "based on a real documented process of the Inquisition".

Logically, the author poses an attractive plot: "A child is found dead in his crib. His body, with strange signs and bruised, soon becomes irrefutable proof for those looking for culprits. A young maid known for her love spells and her closeness to an unstable couple. What begins as a domestic drama ends up before the judges of the Holy Inquisition, shrouded in superstitions, rumors and confessions that are only uttered in the torture chambers".

As we have just shown, the author plays with various commonplaces and set phrases attributed to the Inquisition tribunal in order to attract readers. This will become increasingly difficult as history books and teachers explain to students the reality of the inquisitorial process.

First of all, let us recall that the Tribunal of the Inquisition was set up in Castile in 1478 by Pope Sixtus IV to investigate ("inquisitio" means investigation) the crime of Judaizing heresy that had spread in Castile since the massive conversions of Jews in Castile since 1390.

The objective of the inquisitorial process was to determine whether the "supposed heretic" had really committed a crime of heresy, that is, whether he was a formal and material heresy and whether he was persistent in his heresy or not. As is known, the crime of heresy was considered a crime of "lèse majesté". If counterfeiting currency was a crime of "lèse majesté" punishable by death, in the same way, counterfeiting the faith was also considered a crime of "lèse majesté" and, if the defendant was persistent in heresy, he could be handed over to the secular arm for execution.

If changing the faith by denying some of the articles of the creed was a sin of heresy, apostatizing from the Christian faith adopted by baptism to return to the law of Moses would be the worst of heresies: apostasy.

At a time when the Catholic kings were seeking the unity of the kingdoms of Spain under the crown, unity in the faith was considered capital for the maintenance of the kingdom. In addition, faith was the most appreciated value in society and the most sold books were the Bible and the "ars moriendi", how to prepare oneself to die well in order to reach heaven.

The Holy Father John Paul II in a moving ceremony on March 12, 2000 asked forgiveness for all the sins of all Christians of all times and especially for the use of violence to defend the faith.

This is the theological error of the Inquisition, to force the conversion of the heretic, to procure his repentance under the threat of the death penalty for the obstinate heretic. Heresy was the worst social sin.

Finally, let us remember that the Spanish Inquisition paid little attention to witchcraft. First, because it was not a heresy, but a sin against religion, and also because in the few cases that were studied in the Tribunal of Logroño in the sixteenth century, it was found that the defendants usually had mental problems.

The Inquisition was abolished by the Cortes of Cadiz and later by King Ferdinand VII in 1834. But the Inquisition left behind an even more serious error, which was the inquisitorial mentality that leads to impose distrust on those who stray from the true faith, instead of trying to attract them back to the truth through persuasion.

On behalf of the Holy Office