ARTISTIC COMMENTARY

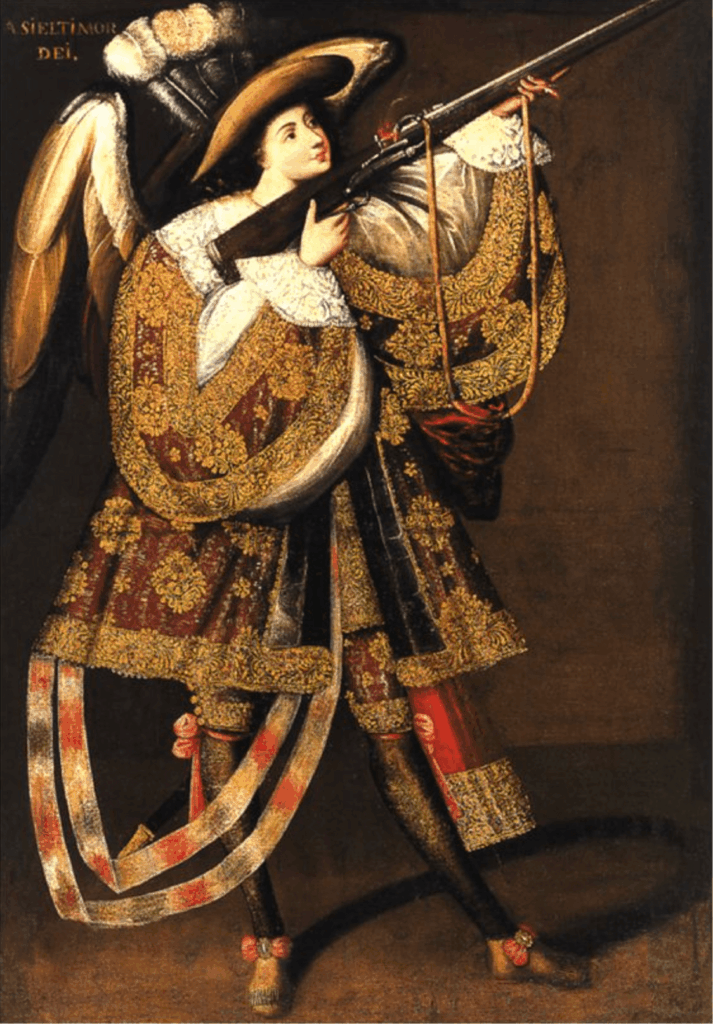

Angels were created by God before man. They are spirits without physical form, which has not prevented them from being depicted in Christian art for centuries. This painting, created in the 17th century by an anonymous Bolivian painter (circle of the Master of Calamarca), certainly does not fit in with the traditional idea we have of them: the title reveals the name of the angel, which appears inscribed in the upper left corner: Asiel Timor Dei, a name unfamiliar to us when compared, for example, to the archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. This particular angel appears alone, occupying the entire pictorial plane; his legs cast their shadow against a neutral background, which helps to create a simple perspective, subtly dividing the space behind him. The clothing is period, very sophisticated, inspired by that of Creole and Andean nobles and aristocrats, with protruding sleeves and a luxurious jacket decorated with lace. The angel has no wings, but has prominent feathers hanging from his hat and is depicted in the act of pointing an arquebus. The palette used is quite limited, based on primary colors with few tonal variations, although there is an interest in detail and the use of gold to emphasize the importance of the character.

A celestial, military, and aristocratic representation

Looking at the painting without any knowledge of its context, it would be easy to think that we are looking at a period figure of someone of noble birth, perhaps a wealthy landowner or a soldier. Nothing, except the inscription with the name (for those viewers versed in Latin and the Bible), indicates that we are looking at an angel.

The Christian theologian Pseudo-Dionysius wrote, “From Coelesti Hierarchia” on angelology and the hierarchies of angels, which influenced medieval theologians. He divided angels into three hierarchies, each containing three orders based on their proximity to God. “The Assumption of the Virgin” Botticini's (1475-76) painting in the National Gallery in London shows a large number of them. The subject was well known in South America; in the former Viceroyalty of Peru, local artists such as Diego Quispe Tito and Basilio de Santa Cruz, or the Bolivians Melchor Pérez Holguín and Leonardo Flores, painted series of military angels carrying different types of weapons: these were custom commissions for distant locations. Our painting is an oil on canvas, which makes the work easily foldable, lightweight, and ready to be shipped to customers in faraway locations, although some are made of wood or copper.

Among these soldier angels are Saint Michael with a spear, with whom we are most familiar, Alamiel Dei with a trumpet and a crown, and the angels Zabriel, Hadriel, Leitiel, and Laeiel carrying arquebuses in different positions, among many others. The angels appear wielding all kinds of weapons of the period, but they are not depicted in battle. Their size varies between 120 cm and 2 meters in height.

Angels with arquebuses

All these characteristics give the paintings a unique style and original appearance. The prolific use of the arquebus and the distinctive features of these paintings explain the name “Arquebusier Angels.”.

This type of angel could have a connection with the ancient winged warriors of the pre-Hispanic pantheon. They may also have been inspired by Dutch and Spanish engravings of the time and by the widespread devotion to guardian angels. This shows that Western art was known in these lands, but local artists chose to mix it with their own representations inspired by the indigenous art that was more familiar to them. This is one of the great characteristics of art: the ability to adapt well-established models to new contexts and to the mentality of different peoples, conveying similar messages in a different visual form. These representations were widely disseminated because they resembled regional tastes.

CATECHETICAL COMMENTARY

The angelic figure, so splendidly dressed and armed, that we see in this painting expresses the Church's enduring belief in the existence of angels and their mission. Indeed, the Creed professes faith in the Creator of the earth and all that is visible (so well represented in Bosch's triptych, which we are already familiar with) and, at the same time, of heaven and all that is invisible. Both creations, although bearing different fruit, are simultaneous, but theology normally explains first the heavenly, or invisible, or spiritual, or angelic creation (which can be called by all these names), and then the earthly (or visible, or corporeal) creation. The reason for this is the excellence that Christian tradition has attributed to the spiritual over the sensible, as expressed, for example, by St. Thomas Aquinas in question 50 of the first part of the Summa Theologiae.

A transcendent savior figure

However, in the field of catechetical expression of faith, which is the focus of this series on Christian art, it is usually more pedagogical to begin with the visible creation, which is our first experience through the senses, and then move on to the invisible. Having explained the second place occupied in this series by Asiel's fascinating canvas, we can begin our explanation by considering the dark background that makes it stand out. In addition to being a suggestive pictorial device, it expresses that angels move in an invisible sphere, closer to the transcendent presence of God than the human sphere can reach with its mere natural forces. The darkness evokes, as in Bosch's triptych, that world which transcends human representation, just as the floral and luminous backgrounds that appear in other canvases of archangels remind us of their closeness to the visible world.

In fact, spiritual creatures, created like visible creatures by the Word of God, are at the service of the saving plan with which God, in Christ, has redeemed the entire creation. As St. Paul reminds us (Col 1:16), the invisible world was also created for Christ, and therefore they enter into his saving work as servants belonging to the invisible world destined for the good of the material world. This relationship of angels with material creation, especially with human beings, who are both spiritual and corporeal, is concretized in their mission as messengers and protectors.

In Sacred Scripture we find numerous examples of the first mission, such as the frequent appearances of the Angel of the Lord in the Old Testament or the presence of angels as the first heralds of the Resurrection in the New Testament. The mission of protection, which also appears in numerous passages in both testaments, is expressed in this painting with the original figure of the soldier. A soldier, incidentally, who is not in the lower ranks of the army but, as his sophisticated attire, as luxurious as that of the great colonial nobles, shows, belongs to the excellent corps of the invisible army. It recalls one of the appearances of the Angel of the Lord to Joshua (Joshua 5:13-14): “Joshua looked up and saw a man standing in front of him with a drawn sword in his hand. Joshua went up to him and asked, ”Are you one of us or one of our enemies? ' He replied, 'No, I am the commander of the army of the Lord, and I have just arrived. Joshua fell face down to the ground and worshiped him.".

Protectors against evil

In Jewish tradition, inherited by the early Christians, angels protect God's people as powerful and noble warriors, as we can see in this quote from the Old Testament, and also in the Qumran writings, the apocryphal writings of Judaism, and the Book of Revelation itself. St. Paul himself reminds us that we need a very special strength and military equipment, “for our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the principalities, against the powers, against the rulers of this world of darkness, against the evil spirits in the air. Therefore, take up the weapons of God so that you may be able to resist” (Eph 6:12-13).

This archangel musketeer conveys with great forcefulness how well protected we are by the invisible world against the aggressions we encounter in life itself, especially those suffered at the hands of evil spiritual beings opposed to God (demons). But this archangel not only carries a powerful weapon, he also has a mysterious name: Asiel, which means fear of God. That the name of the Archangel expresses his mission is known thanks to the popularity of the three major Archangels: Saint Michael (Who is like God?), Saint Gabriel (Messenger of God) and Saint Raphael (Medicine of God). The name and mission of this archangel, however, are not easy to trace.

This is due, once again, to borrowings that Christian tradition took from Jewish tradition since its origins. In Judaism, speculation about the names of angels and their missions reached a very high level of development. Given the pressure of the evil presence in the world, there was a perceived need to know who the protectors of the faithful were and what each one's role was. Knowing the name of the archangel served to invoke him with the certainty of being heard. Knowing his mission was a guarantee of turning to the right intercessor on each occasion. On the other hand, knowing the name of a demon gave the ability to conjure him and neutralize his evil power, while it was very useful to know which demon was behind each evil suffered in order to identify the enemy.

From the long lists of angelic names in Judaism, Christian tradition took many names in a somewhat chaotic manner, so that the repertoire of angels to be painted presents a variety as wide as it is disordered, with the exception of the three Archangels already known. The presence of the angelic name and its meaning in this canvas, in short, reminds us how, since time immemorial, Christian tradition, including that present in Latin America, has recognized angels as the powerful invisible servants of Christ, who, in addition to carrying divine messages to the faithful, protect them with the excellence of their spiritual power expressed in their names.

Work

Art historian and Doctor of Theology