The work of Luna Miguel (1990), a successful writer and editor and one of the best writers in Spanish literature today, I found it very interesting and very timely, because the issue addressed, literary censorship, is not a matter of Franco's times but, as the author shows, censorship is inside us, from the factory.

The origins of the critical sense and internal censorship

In fact, St. Basil the Great (p. 330-379), one of the great fathers of the Church in the fourth century, when the Church had already obtained a charter and could therefore express itself with complete freedom, is the first to address the young people of his time and of all times to speak to them about critical sense at the time of reading the Greek and Latin classics that they will be able to read when they enter the schools of Rhetoric and Oratory to begin their formation.

The advice that has transcended all times and cultures is of great wisdom: it is necessary to read a lot in order to learn to know who God, man, the world and nature are and thus to be able to govern the world that God has given us as an inheritance (Dt 3:18) and, therefore, to live together with others will build the kingdom of God and, finally, to acquire the necessary wisdom of life with which to bring to our time the values and gifts we have received from the family and our teachers.

The second piece of advice, even more concrete, was to know how to draw from books all the greatness they contain in order to build in ourselves the greatness of the dignity of the human person, of every human person of every class and condition. Logically, as a believer, he added that the greatness of the person is based on being the image and likeness of God. At the same time, it is necessary to know how to elegantly set aside anything that attacks the dignity of the human person, or diminishes or diminishes it in any way.

Luna Miguel's experience with Lolita and censorship

Luna Miguel will tell us on this occasion in first person, the genesis and development of a lecture that she had to give to a university audience on a topic as broad as censorship and pleasure, within a cycle of literature and eroticism.

He then explained that in order to be able to say something valuable so that those attending the conference could take away from the presentation any idea of interest, it occurred to him to give the personal example of what had happened to him and his environment when, after much effort, he had managed to get hold of the novel by the Russian Vladimir Nabokov, published in the United States in 1955, which narrated the adventures of the protagonist, an obsessive man, Humbert Humbert, in his adolescence he had managed to get hold of the novel by the Russian Vladimir Nabokov, published in the United States in 1955, which narrated the adventures of the protagonist, an obsessive man named Humbert Humbert, who had fallen madly in love with a 14-year-old girl named Lolita and ended up marrying Lolita's mother in order to get close to the girl and take advantage of her.

First of all, Luna Miguel reduces the climate of tension that he would have created in a few short pages, that is, he explains crudely that the novel is much more propaganda than reality, because after a few years neither the subject matter was so crude, nor the narration is so explicit, and finally the exposition is not so credible either. That is to say, that nowadays its reprint would not have any success.

Evidently, the most interesting part of this work is the bibliography that he has incorporated at the end of the book, since it shows that he has given a lot of thought to what he has written and, above all, he has expressed it with good humor, maddeningly and documented.

Logically, he will provide us with all the information he has been able to gather about the impact of the famous contemporary novel that, according to the New York Times at the time, became a worldwide “best seller” and was translated into all Western languages.

He will also tell us about the scandal that the hippie movement and world pacifism due to the Vietnam War caused in large sectors of European and American society, ten years after the end of the Second World War, when secularization was slowly advancing and almost ten years before the revolution of sixty-eight.

Reflections on freedom, literature and women.

As the author clearly explains, in a very personal way, the book now has much less shrapnel than many works that are being published everywhere, television series, etc., both in terms of the subject matter and the way it is written.

In any case, it is interesting that the advice received by the author when she was a teenager, whether from her parents, the librarian or her literature teacher, was to wait a while to read it in order to have the necessary training, more complete criteria and critical capacity to extract from the book what was necessary to better understand the dignity of the human person and to reject what would diminish it.

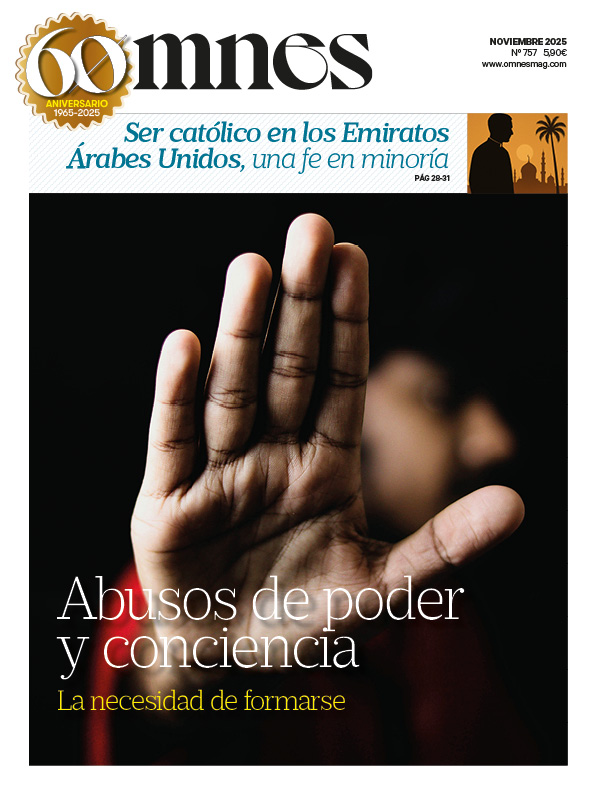

In the background of this interesting work, it is clear that there is still a lot of tension in everything that refers to the treatment of women in literature, the audiovisual world or art in general. Evidently, there is a lot of mistrust in this book: “Let's not be naive. We have not yet broken the glass text. It is enough to know a little of the history of our gender to realize that behind the advance of our rights and freedoms there is always a wave of iniquity that forces us to retreat” (p. 33).

Admittedly, the work will gain momentum and eventually turn the subject of Lolita into a knot of interesting comments: can one distinguish the work from the author? Can one read this work without drawing the obvious conclusion that psychological abuse is wrong? (p. 37). This work will get “complicated” at times, but it also provides thought-provoking arguments for both novel readers and authors.

It is interesting that our author, in a moment of raving, writes some words that summarize a senseless complaint against common sense: “it didn't matter if they censored it, she had them in her head and therefore she would rewrite them if she felt like it; to put an end to literature, they would first have to put an end to her” (p. 72-73).

And, putting Simone de Beauvoir in line with the Marquis de Sade, she will affirm: “De Beauvoir saw in the various misunderstandings provoked by the pornographer's work a form of murder. To forget her literature or to reduce her life to a couple of anecdotes was, on the one hand, that which would destroy her thought, but also that which, ironically, would save her name from the fire” (p. 95). Moreover, she will affirm: “the history of literature is the history of our addictions, I thought then, right there, at the stroke of midnight, with the enormous sadness of being alone” (p. 117). Shortly afterwards, she will end this work with these significant words: “It will be up to you to decide whether you want to participate in this unthinkable delirium, or whether you have only come to understand it” (p. 211).

Incensurable