We have all heard about St. Paul of Tarsus and his adventures: travels, adventures on land and sea, shipwrecks, dangers. His life seems more exciting than a television series. For centuries, his name has evoked faraway countries, new languages and people, never known before, sun, salty air and wind that caresses the face. At his birth, in Tarsus, he had been called Shaul - the impetuous one - but it was with the name "Paul", a little man, that he became universally famous.

We talked about it with Giulio Mariotti, Judaist and biblical scholarThe author, who works in the field of Second Temple Judaism and Christian origins, studying the history of Jewish thought and the nascent movement of the disciples of Jesus.

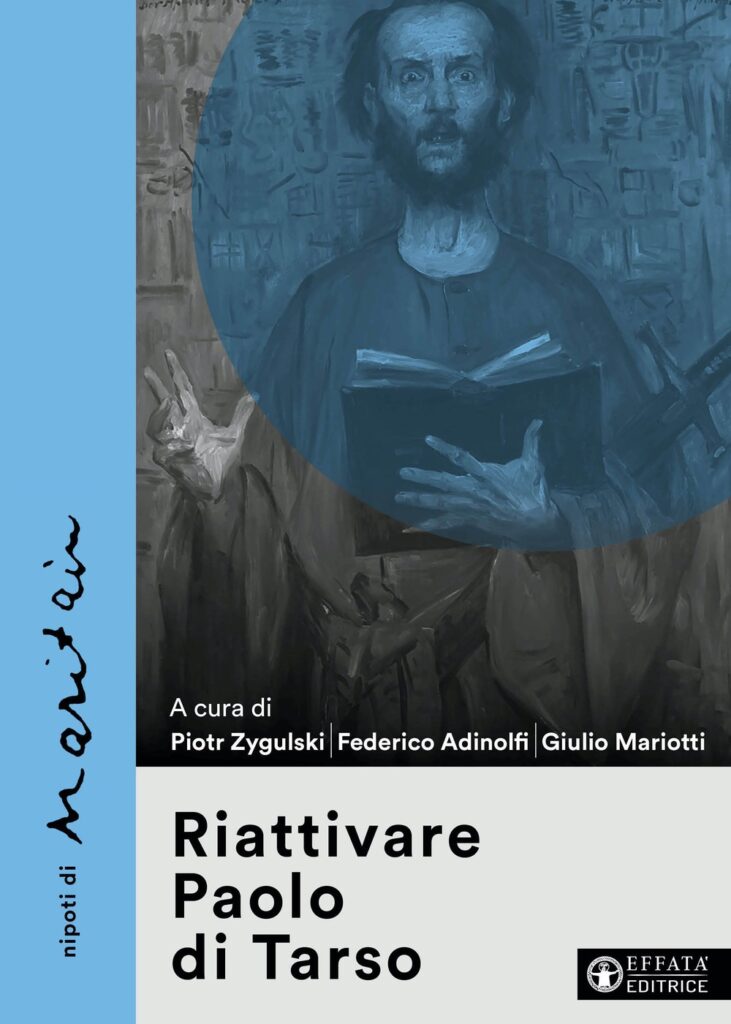

He is co-author with Gabriele Boccaccini of "Paul, a Jew of His Time" (2025), co-editor with Piotr Zygulski and Federico Adinolfi of the compilation volume "Reactivating Paul of Tarsus" ("Reactivating Paul of Tarsus", 2025), and author of "Election, Dualism, Time. Reading 2 Thessalonians in the Judaism of his time" (2024).

Omnes interviews him to understand what it means today to read Paul again without prejudice, and how his proclamation can continue to speak to people.

In "Reactivating Paul of Tarsus" (Effeta, 2025), you have gathered contributions from international theologians and scholars to bring Paul out of confessional and academic confines. Why did you choose the verb "reactivate" to speak of Paul? What needs to be reactivated today in his figure?

- We have chosen the verb "reactivate" because it is not simply a matter of studying Paul anew, but of giving him back a vital voice in today's cultural, social, theological and interreligious debate. To "reactivate" means to take Paul out of an exclusivist Christian reading and place him once again at the center of a pluralistic and shared reflection. For too long he has been read as an apostate from Judaism and founder of Christianity. With this verb, we wanted to emphasize that Paul is not a figure of the past to be exhumed, but a voice that is still capable of questioning our certainties and systems.

Reactivating Paul means offering new spaces to perspectives that until now have received little attention in Italy, such as the reading of Paul within the Judaism of his time. Thus, in addition to the fundamental studies of authors such as Romano Penna, Mauro Pesce, Antonio Pitta and Gabriele Boccaccini, to cite just a few scholars, others are being added on the Judaism of the Apostle that incorporate both the Italian and international research tradition.

In his studies on Paul he insists that he never "abandoned" Judaism. What changes if we really read him as a believing, observant, apocalyptic Jew?

- To read Paul as a believing, observant and apocalyptic Jew is to dismantle one of the pillars on which Christian theology was based for centuries: the idea that he broke with Judaism to found a new universal, spiritual and, ultimately, "superior" religion.

In reality, Paul never abandoned Judaism: he is a Pharisee who adheres to an eschatological and messianic movement within the Judaism of his time, convinced that in Jesus a definitive phase in the history of Israel and humanity has been inaugurated. He neither rejects the Torah nor considers it useless, but interprets the present time as an "eschatological moment" in which even the Gentiles can become part of the people of God, Israel, without having to become Jews, the whole of Israel that will be saved (Rom 11:26). In this way, Paul is once again not the destroyer of Judaism, but simply one of its voices in the Judaism of his time.

In this volume you have collected essays that bring Paul of Tarsus into dialogue with topics such as gender equality, ecology or social injustice. Are we not in danger of projecting too many things of our times onto him?

- It is a very fair question, and we are fully aware of it. The risk of anachronism exists whenever we try to "update" an ancient author. However, it is not a matter of pretending that Paul spoke of ecology, gender equality or global justice as we would today. That would be ideological and historically incorrect. Our intention is different: to start from the principles of his thought to ask ourselves if they can still say something to our time.

Paul raises radical questions-about evil, about the meaning of the law, about hope, about the universality of salvation-that remain alive even today. It is therefore legitimate to ask ourselves: what can his way of thinking suggest to us, also in the field of rights, politics and care for creation? Not to modernize it by force, but to allow us to question it.

Is there any Pauline verse that has accompanied you and accompanies you especially in this moment of your life?

- The verse that accompanies me most at this moment is: "For when I am weak, then I am strong" (2 Cor 12:10). It is a phrase that subverts all the logics of power, success and performance that dominate our lives. In a world that demands that we always perform, always win, always be impeccable, Paul reminds us that it is precisely in weakness that the power of God is revealed.

Within the apocalyptic worldview, Paul believes that divine intervention is necessary to resolve the problem of evil, and this is what he found in what is described as a revelation on the road to Damascus. This realization, together with that of being at the end of time, will guide the whole of Paul's thought and offers us the realization that, even in our time, the trump card consists in showing fragility rather than performance at every opportunity.

Why is it no longer possible to speak of Paul as a convert?

- To speak of "conversion" for Paul, in the traditional sense of passing from one religion to another, is historically and theologically misleading. In Paul's time, Christianity as an autonomous religion did not yet exist. Therefore, Paul did not abandon Judaism; he never disavowed the Torah or his Jewish identity. He himself proudly described himself as "a Jew, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Pharisee in the observance of the law" (Phil 3:5).

What is experienced on the road to Damascus, therefore, is not a religious "conversion" but a prophetic call in the manner of Jeremiah and Isaiah read as a revelation. To continue to speak of "conversion" perpetuates a theology of rupture that has nourished Christian anti-Judaism for centuries. It is time to replace this language with more historically and literally appropriate words: "call" or "revelation".

Paul did not change his religion: he changed his position while remaining within Judaism. For this reason, for some years now, the Secretariat for Ecumenical Activities has been proposing to change the name of the feast of 25 January from "conversion" to the feast of Paul's "vocation.

You have also included Jewish and secular voices in the volume. Why is a confrontation that transcends the Christian sphere important today?

- To speak of Paul today can no longer be an internal affair of Christian exegesis and theology alone. For too long Paul has been read and used only from an ecclesial point of view, often in a polemical and anti-Jewish key. However, he himself has always defined himself as a Jew - a Pharisee, an observant Jew - and has never denied this identity. That is why it was essential in this volume, as it is in international research and debate, to open the dialogue to other voices: to Jewish scholars and lay thinkers, and to anyone interested in investigating who Paul really was without prejudice or preconceived ideas.

It is also a way of overcoming confessional barriers and inviting everyone-believers and non-believers alike-to confront a figure who, no matter how you look at it, has profoundly marked the history of Western thought. Paul does not belong to a Church but, like all great thinkers, to humanity.

What can the Jewish world receive from a re-reading of Paul of Tarsus such as the one you propose?

- One of the great potentials of Paul's perspective within Judaism is to finally open a way for a non-hostile reception of Paul also by the Jewish world. For centuries, in fact, Paul was perceived as the one who betrayed Judaism, condemned its practices and founded a separate, substitute and often hostile religion.

This image emerged especially from the second century onwards, and then became consolidated in Christianity as the "standard view", almost up to the present day. But today historical studies tell us otherwise: Paul never wanted to found another religion, nor did he seek to abolish the Torah. He remained within Judaism, in dialogue and sometimes in tension with other Jewish groups of his time.

What do you wish for those who read this book, especially if they are young or alienated from the faith?

- My sincere hope is that those who read this book will encounter a Paul who increasingly resembles his authentic face, stripped of centuries of interpretations that have turned him into a model of Christian anti-Judaism or exclusivist intolerance. The hope is that we will understand that Paul escapes labels and can be appreciated by believers and non-believers, by Christians and Jews alike.