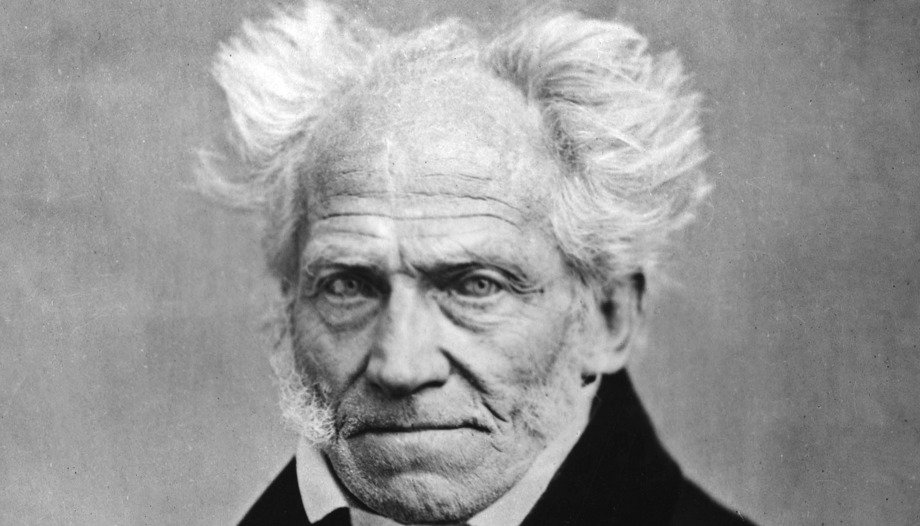

It is worth reading again "Schopenhauer and the Wild Years of Philosophy", the magnificent work of Rüdiger Safranski (Rottweil, 1945), about the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), recently republished, since biographical studies of the great German thinkers of that period often shed much light on their main philosophical theses.

Particularly important are the biographical insights in the case of Rüdiger Safranski's historical studies. He is highly valued in this respect for his profound knowledge of the history of ideas and especially of the period he calls "the wild years of philosophy" (387-404).

Undoubtedly, Schopenhauer, a self-made philosopher who contributed important ideas to the history of thought, is right when he said: "Who can ascend and then be silent" (76). Interestingly, as a young man he had written: "If we take away from life the brief moments of religion, art and pure love, what is left but a succession of trivial thoughts" (90).

As is well known, thinkers tend to fall in love with their ideas, as when Kant invented an extraterrestrial God that could be adopted as such by agnostics and deists distrustful of the Church and of God himself, who ended up depriving the German enlightenment of confidence in God (91).

The life of Schopenhauer

It is very interesting the development of the biography of Schopenhauer and other authors of that time, such as KantHegel and Hölderlin. Also, the study of the French Revolution and its reception in Germany, until they were invaded by Napoleon's troops, their cities sacked and turned into a trail of blood, violence and desolation that turned the idyllic ideas of the revolution into disappointment and hatred of the French that has endured to this day in some layers of German society (122).

Of great interest are the pages devoted to the education and training of the young Arthur Schopenhauer and his sister Adele, who was frail throughout her life, by their wealthy widowed mother. Finally, Safranski comments: "It is clear that the freedom his mother granted him was too great for Arthur. But his pride forbade him to confess it to himself" (133).

In this matter it is worth noting that, in the house of Johana, Schopenhauer's mother, there was a salon where the ladies of high society came to talk and listen to the city's leading men, especially Goethe who frequented the house and focused everyone's attention, especially Arthur's (135) with whom he would end up falling out (251).

Once Schopenhauer came of age and his mother died, he would become a rentier who would live off the inheritance and would manage it skillfully in order to live soberly but not depend on anyone or any official position where he could teach and earn money.

On the other hand, after some first moments of courtship and approach to some women of his time, he would end up closing himself in his philosophical creation and not only did he not form a family but he had little contact with other authors of his time.

Schopenhauer's Impact on Philosophy

With respect to his contribution to the philosophy of his time and to the history of philosophy itself, being outside of academic environments and the scarcity of his works throughout his life, his fame and the interest aroused by his ideas will take time to consolidate and it would almost be necessary to wait until his death to talk about him.

In the first place, Safranski will characterize the devastating encounter with Kant who had destroyed traditional metaphysics by means of a system whereby "metaphysical transcendentals do not refer to the transcendent: they are merely transcendental" (...) They are only of interest for epistemology: "transcendental analysis consists precisely in showing that we cannot and why we cannot have knowledge of the transcendent" (150). He then adds that Kant will undertake an enterprise aimed at dealing with how objects are known, without being interested in the object (151).

Schopenhauer, enthusiastic about Plato, wrote about Kant: "the best way to designate what Kant lacks is perhaps to say that he did not know contemplation" (156). Undoubtedly, locked in subjectivism, he never saw beyond his intellectual construct of his own self (156). Finally, he will end up knowing "the Kant, the theorist of human freedom" (157).

In 1813, Arthur Schopenhauer went to Rudolstadt via Weimar to write his doctoral thesis "On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason", which would establish him as a philosopher.

The will

Years later, he will write his most famous work, indebted to his doctoral thesis on "better consciousness", with the famous title of "The World as Will and Representation". In it, "he will remain Kantian in his own way in order to remain Platonic in his own way as well" (206).

It is very interesting how Safranski prepares the reader to discover the key to Schopenhauer's new philosophy on the "secret of the will", that is, a will in one's own body, lived from within, like an arrow, like iron attracted by the force of the magnet: "with the discovery of the metaphysics of the will, Schopenhauer finds a language to express this vision; this language will give him the proud confidence that allows him to radically separate himself from the whole philosophical tradition and from his contemporaries" (217).

A discovery, full of extraordinary radicality, he writes: "The world as a thing in itself is a great will that does not know what it wants; it does not know, but only wants, precisely because it is will and nothing else" (266).