ARTISTIC COMMENTARY

The Triptych of the Garden of Delights is made up of three oak panels. The two wings are folded over the central panel, a continuation of the landscape of the Garden of Eden. The bright colors of this composition contrast markedly with the right panel depicting hell. When the triptych is closed, all we see is a grisaille representation of the creation of the world (analyzed previously).

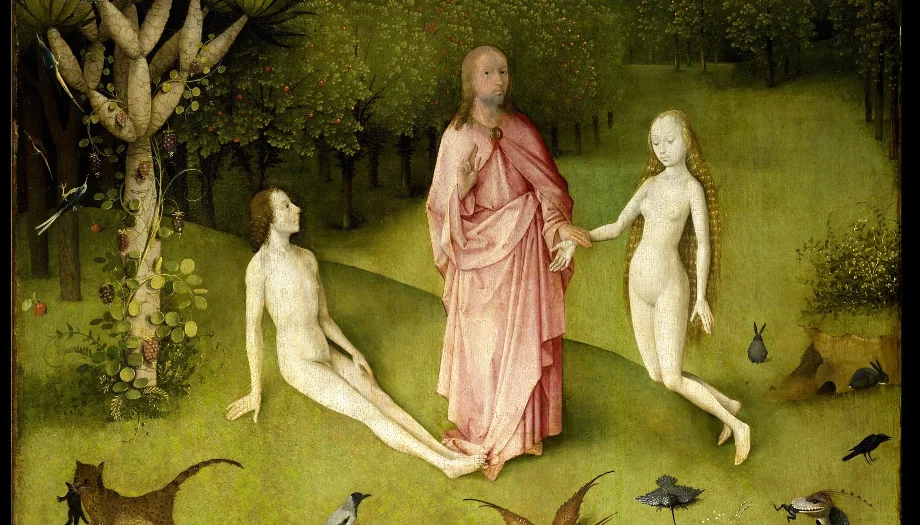

The scene shows God the Father making the presentation of Eve to Adam, an unusual subject (Bosch initially included the creation of Eve, as the technical analysis of infrared reflectography reveals).

Symbolism in Eden

The high horizon line allows for a panoramic composition featuring three overlapping planes alternating bands of blue and green to create a sense of perspective. The sky is reduced to a cold mountainous band that gives depth to the landscape through the use of aerial perspective (a bluish haze in which objects fade due to distance). Bosch's interest is in the narrative and iconographic program. What seems a rather naive representation of paradise is, on the contrary, full of meaning. We can appreciate the aesthetic merit of the painting, the detailed depiction of a vast array of vegetation and different types of creatures inhabiting the newly created world, enhanced by the use of oil paint traditional at the time. The pink robe of God, the only clothed figure in the composition is modeled in the Flemish style. The other pink object is the fountain in the center of the panel, in a straight line above God: a probable allusion to the source of the water of life coming from God's throne. To its right, a palm tree with a coiled serpent is the only reference to the fall and sin in this panel. It is interesting to note that the tree of life to Adam's left is a copy of a dragon tree from the Canary Islands, known in Flanders from engravings (The Flight to Egypt, Martin Schongauer, c. 1470-75).

Adam and Eve: Foreshadowing of Christ and the Church

The scale and centrality of the three main figures underscores the importance given by Bosch. Many depictions of Adam and Eve usually show Adam sleeping during God's creation of Eve, but in this creation scene, the iconography has been modified. Adam's feet are crossed, touching God's foot, with his legs extended. For viewers in the Middle Ages, this was easily associated with depictions of Christ on the Cross. God holds Eve's hand as she kneels before Him, a scene that has parallels to the institution of marriage: God instituted marriage-human love-and instructed them to be fruitful and multiply (shown in the central panel, Paradise). Christ, here depicted as Adam, was seen as the bridegroom, who, together with his bride, the church (the “New Eve”), restored this institution through the reunion of humanity and God on the Cross. The medieval message was probably known to Bosch, here representing the future marriage of the bridegroom and bride as a restoration of the “image and likeness” to God in which Adam and Eve had originally been created.

This interpretation of symbolism requires a certain level of education of the viewer. We do not know much about the commission of this triptych. The meaning is clearly moralizing, but the fact that it includes nude men and women, in groups or couples, having amorous relations in a clear allusion to sin, might not seem appropriate for display in a church. The panel is first mentioned in 1517, by Antonio de Beatis, who places it in the palace of Nassau in Brussels. We can think that the intended audience would be a scholarly audience, who would be able to read between the lines of this beautiful painting, designed thanks to Bosch's power of invention: his creativity was a distinctive feature, which made him stand out among other painters and which did not go unnoticed by Philip II.

CATECHETICAL COMMENTARY

The first chapter of Genesis presented God's creative work as the design and construction of a marvelous scenario in which the history of humanity could be represented. In this painting, Bosch presents us with the second part of this work, which in the terminology of the medieval theology that inspired the painting could be called opus ornatus (the fourth to sixth days of the Creation), the work of clothing a world already structured in the distinction (the first to third days of the Creation), which was represented in the closed panels of this painting.

Bosch does not represent here the work of the fourth day, the celestial luminaries, but deploys all his artistic energy to give a complete image of the fifth day (when the sea gives rise to fish and birds) and the sixth (when the earth produces the animals that inhabit it), in which the visible creation culminates. The world painted here overflows with a diversity of species and shows a careful arrangement of living beings. The lower part of the painting, on the other hand, expresses in the artist's own enigmatic symbolism the complex interrelation that exists between them.

The interesting balance achieved between the careful and orderly composition and the inexhaustible and unimaginable diversity of plants and animals, is expressing very well that the Creator wanted to endow his work with order and diversity, leaving in each of the creatures, and in the interdependence that exists between them, a reflection of his goodness and perfection; in short, a brief reflection of his infinite beauty.

The use of a high horizon, which leaves plenty of space for the representation of the visible creation, is like an evocation of the immensity of the created world (reinforced by the distant aerial perspective) and of its diversity. This is manifested not only in the number, but also in the strange animals that swarm through the painting, which perhaps owe their fanciful forms to the news of the strange animals that the Castilian and Portuguese maritime expeditions were discovering at the end of the 15th century. This admirable scenery, thus painted, is destined in the first chapter of Genesis for humanity, which is its center and meaning.

A custodian for a paradise

However, to situate the creation of humanity, Bosch, like the vast majority of the Western pictorial tradition, resorts to the second chapter of Genesis. In it, a reverse order is followed: in a desert world, in which only God and a spring of water (both present in the painting sharing the color pink and the central situation that gives them presidency) the human being is modeled, and only then a paradise of plants and animals is planted for him to guard it.

For those who contemplate the picture from this chapter that gives it meaning, it is clear that all the immense wealth of diversity and order that God has painted in the world is offered to humanity as a stage, as a gift, and also as a responsibility and a task. The human being is called to discover and value the order and goodness of creation, as well as to respect the correct interrelationship between creatures and their delicate balances. The human being is placed on center stage, not as an actor who is going to show off and take advantage of him; if a garden is planted for him, it is not for him to abuse and ruin it. In this scenario, man and woman must play their role as custodians of Creation in respect for it and in immediate relationship with its Creator.

The relationship as an essential element of the human being, in his condition as a person created in the image of the Creator, is expressed in the significant look that Adam directs to God in response to the blessing he is receiving from his right hand. Humanity receives the gift of being created, therefore, in view of communion with God and his covenant with Him, a destiny that will be fully fulfilled in Jesus Christ, the New Adam, who will make it possible for this covenant in faith (by which the human being serves and loves God) to be fully realized.

Equal and complementary

It is also significant that, with his left hand, God takes Eve's hand to present it to Adam. In effect, it expresses that the relationship of the human being with the Creator must also be lived in the personal relationship with his fellow human beings. On the other hand, as the second chapter of Genesis teaches, the relationship between man and woman is not only one of communication, but of complementarity: none of the numerous creatures that inhabit the picture is sufficient to complete the desire and the personality of the human being. As the reader of Genesis already knows, only Eve is the adequate help for Adam.

God makes all creatures pass before Adam, but none completes him, but only the woman he has created for him in equality of value and dignity (both have the same size in the composition, and appear referred to each other, through the mediation of the Hand of the Creator). If male and female require each other with the diversity and complementarity willed by the Creator and carefully captured in this picture, it seems clear that protecting their union is fundamental not only for the biological survival of the human species, but also for each person to find the fullness of the human vocation in the free and sincere gift and surrender to another person.

Hence the evocation of the sacrament of Matrimony, which remains as if drawn by the two divine Hands, which unite and bless. The same Hands of the Creator that molded humanity from the clay of the earth, according to the second chapter of Genesis, are those that in this picture build, bless and protect the union of the human couple, so that in their union the work of the Creator of humanity may be fulfilled.

Man and woman are thus in harmony with each other, with the Creator and with the whole of creation, living the state of original justice that the serene composition and the soft chromatic tones of the painting evoke. However, the presence of the serpent in the tree, still distant but already threatening, reminds the viewer of the fragility of this harmony, which the Hand of God must protect and will have to repair, once lost in the way that will be narrated in the next painting of this series.

Technical data of the work

Art historian and Doctor of Theology