- Kimberley Heatherington (OSV News)

Transhumanism is an extremely topical term. It appears repeatedly, with intrigue, and also with a certain threat. What exactly is transhumanism? Because it gives the impression that it pursues a sort of digital immortality, with an anti-human ideology.

A May 15 discussion from the Institute for Human Ecology at The Catholic University of America in Washington offered immediate insight with the title "Transhumanism: The Ultimate Heresy?"

The panelists were scholar Jan Bentz, professor and tutor at Blackfriars Studium in Oxford, England. Wael Taji Miller, editor of the Axioma Center, the first faith-based Christian think tank in Hungary. And Legionary of Christ Father Michael Baggot, professor of theology and bioethics currently teaching at the Pontifical Athenaeum Regina Apostolorum in Rome.

Transhumanism, not just new technology

Each argued, through the expertise of their respective disciplines, in this direction. Transhumanism is not simply a technological project, but rather a modernist heresy that seeks to replace the human person with a machine-enhanced, artificially engineered being.

And if that sounds like the stuff of science fiction - it still is to a large extent - but that doesn't mean it's not an eventual threat to human dignity that Catholics can comfortably ignore.

As a kind of ideological twin to transhumanism, said Jan Bentz, utopianism sees man as self-sufficient and independent of the divine and rejects any permanence of human nature. It confuses progress with redemption, and substitutes metaphysics, questions about reality and existence, for ideology.

"Utopianism," Bentz proposed, "is the obstinate post-Christian denial of man's fallen condition, and the rejection of the historical, social and moral limits that must be recognized in any just political order." Or it is also, he continued, "an obstinate confusion of temporal progress with eschatological redemption (end times)."

A kind of religion without religion

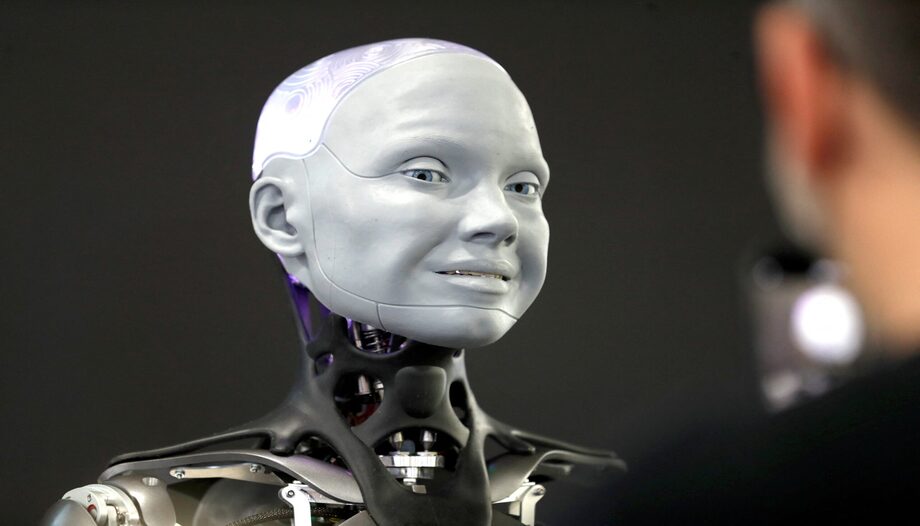

In short, it is a kind of religion without the religion. Indeed, as the panel's own description succinctly noted, "the modern transhumanist movement is presented as the next stage in human evolution. An inevitable leap toward superintelligence, immortality, and transcendence of biological limitations."

"However, beneath the veneer of technological optimism lies an ideology. profoundly anti-humanAn attempt to reject nature, morality and the created order in favor of a utopia of self-deification".

But why is the idea of utopia, which we are perhaps conditioned to think of as a positive good, an equivalent of happiness, a heresy?

"Utopia is a perennial heresy, because ... it attempts to realize the city of God on earth," Bentz simply said. "It attempts to establish paradise on earth. Most utopian rhetoric thrives on this central idea: the utopian and the transhumanist will rarely talk about the negative side effects," he added. "And the collateral damage that comes with their political agenda and even their ideological or philosophical agenda. They will talk about the positives, but not the negatives."

Transhumanism, obsessed with death

Wael Taji Miller, who is also a cognitive neuroscientist, pointed to the transhumanist obsession with death as a kind of defect, a genetic flaw or malfunction mistakenly written into human existence.

"Somehow, in this fear of death that transhumanists seem to embody, consciously and unconsciously, there seems to be this desire to leave the rest of us behind," Miller said. "We will be left behind, and they will achieve transcendence, transcendence of the only kind that really matters to them, which is the escape from death."

And how to do that? "Surely, if the body fails, we can transfer our consciousness to some flesh machine or flesh carrier, repeating this process each time the new body fails. Or maybe even better," Miller said, taking the role of a transhumanist. "We could simply transfer our consciousness to machines of some kind, upload it to the cloud."

It is not a project that Miller endorses.

Not 'no' but 'why'?

"Coming at this from a neuroscience perspective, my answer to this proposition is not 'no,' but 'why?' Neither I nor any credible scientist in the field has succeeded in demonstrating that consciousness itself is transferable," he said. "It is illusory speculation - that is, utopianism - (and) its pursuit, in and of itself, can have very dangerous consequences."

Transhumanism, Miller pointed out, seeks to attain perfection without repentance; to be saved without a doctrine of salvation; and to live forever.

"For me," Miller said, "the way to perfection is through salvation, not through information." The perceived social failure of religion, said Father Michael Baggot, has encouraged some to embrace transhumanism.

For many, religion is "old-fashioned."

"For many, religion is an antiquated set of myths, dreams that have not been fulfilled," he observed. "But, ironically, we find quite often, a kind of quasi-religious tendency or thrust in many secular transhumanists today."

While its ideology seems to share some of the same goals and projects as religion, transhumanism actually claims to progress, rather than offering unfulfilled dreams of a better world.

Transhumanism, Father Baggot said, ultimately hopes to remedy "the perennial difficulties of human nature": aging, disease, suffering and death.

And as they pursue a kind of digital immortality, a posthumanity through large-scale liberation from the limits of the body, transhumanists counsel patience.

Human-machine fusion

"For now," Father Baggot said, they propose that "we need to be content with our meager efforts to extend, little by little, this life, until finally, we can achieve that kind of breakthrough of human-machine fusion, and that exponential explosion of intelligence that will bring about this great liberation from all the weakness and frailty of the body."

But again, there is irony. "Transhumanists have a keen sense of the consequences of sin. Unfortunately, they have lost all sense of the rest of salvation history," he added.

"There is no clear sense of a Creator. Of no objective order, intrinsic to this creation. And therefore, there is no hope of being delivered, through divine grace, from the consequences of these sins," Father Baggot noted, "We are, in many ways in this vision, cosmic orphans, we are left to our own devices."

Kimberley Heatherington writes for OSV News from Virginia.

This article is a translation of an article first published in OSV News. You can find the original article here.