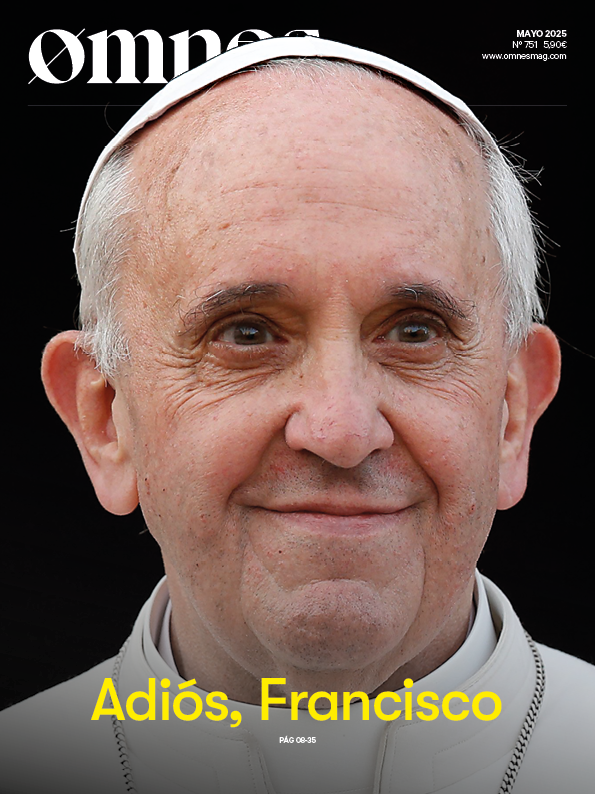

I have read three quarters of the book written by Javier Cercas, a Spanish atheist writer, about Pope Francis in general, and about his trip to Mongolia in particular.

A recurring question arises in the numerous interviews he does with people around Francis, and we could formulate it something like this: if the Pope has been chosen to be a spiritual leader, why does he only talk about earthly topics? The doubt is even more pertinent if we know that the whole book is Cercas' attempt to ask about the resurrection of the flesh and life after death, both of which are indeed purely spiritual topics.

The drifts that this question follows throughout the book are various and interesting, but, above all, they allow us to talk about a theme: that Pope Francis made it clear that we have a problem as readers in the times of algorithms and superficial reading.

I remember once, conversing with a priest friend of mine, who was not very attuned to Pope Francis - or to whom he thought was Pope Francis - he reproached aloud precisely this: that the Pope did not speak about the central themes of the Catholic faith, while he devoted himself to speaking about "political" issues, such as migration, care for nature or concern for the poor. This second statement of his sentence we will leave for another time. But that day, dismantling that parallel reality created by some web page was not difficult, since a few hours earlier the Pope had dedicated his tenth consecutive general audience to a catechesis on the Holy Mass, the central mystery of the Christian faith. Logically, this did not appear in the Vatican information blog that my priest friend read, nor in the headlines of the common press that he saw fleetingly on social networks.

If it was already a problem for the truth that we consume only the information we receive from the algorithms of social networks or from some blog with questionable intentions, now this complication has multiplied with artificial intelligence.

A few days ago it was Mother's Day in many countries of the world and I received several times a fake video of Pope Leo XIV reflecting on the maternal task. Just as my priest friend thought that Francis never spoke about spiritual life, others may now think that Leo XIV is a specialist in cheesy congratulations for the world days of every member of the family.

The task of forming ourselves as readers of news is urgent, because the image we form of the world depends on it. And the same goes for religious information: the task of forming ourselves as readers of news about the Pope is urgent, because the image we form of his person and of the Church depends on it, with clear repercussions also in our spiritual life.

Should we ask a common newspaper, with eminently political themes, to report on the Church with a spiritual sense? Obviously not.

Can we ask the media to give us a breakdown of the Pope's meetings with the religious of the country he is visiting? Obviously not.

Can we ask him to summarize each catechesis dedicated to the different sacraments? Neither.

Each medium looks for what interests its readers. Such a media will look for what is political in the Pope's activities and, passed through the filter of its editorial line, transmit it to its readers. That is its job. If we ask for pears from the elm tree, the problem is ours, not that of this or that newspaper.

A perhaps even more delicate terrain is that of Church information sites. For one might think that one solves one's problem as a reader by visiting websites that are specifically devoted to these topics. However, it is not that easy either.

If one has a little familiarity with these media, one will know that there are those that are often called more "conservative" and those of a more "liberal" bent, with the infinite limitations that these terms have in the religious world. And precisely that we can use those labels is part of the problem.

In most cases, information about the Pope is not given there with a spiritual and supernatural vision of the Church, but rather information about the Church, but soaked with an earthly view, as if everything there were a political struggle, as if the objective in the Church were also to eliminate the enemy, even if, logically, they have to disguise their texts with pious ornaments.

Can we ask them to be open to what the Holy Spirit blows, even if it is something that does not align with their thinking, even if it generates fewer clicks, and even if it does not feed their readers, eager for constant confirmation of their own vision of reality? No.

Everyone is free to produce information as they see fit, but we cannot expect a truly religious perspective from all religious media.

This was one of the realities that Francis unmasked, if only because of the times in which he lived: the need to form ourselves as readers of news. The need to discover the sources, to go to them, to renounce the morbidity of ecclesial politics, to have reliable intermediaries: these are all skills that serve us even for life beyond the religious sphere, especially in times of artificial intelligence.

In those conversations with people who were not in tune with Francis - again: with who they thought Francis was - it was not uncommon to come to this question: How much time have you spent reading the Pope's writings firsthand, and how much time have you spent with the news media that want to keep you hooked on the religious soap opera? Very few people went to the real source and, logically, they were fighting in their minds with a stereotype created in some newsroom.

May this not happen to us with Leo XIV. Thank you," the Pope said in his meeting with the media a few days ago, "for all you have done to abandon the stereotypes and commonplaces through which we often read Christian life and the very life of the Church. It was a polite gesture that perhaps, in reality, conceals an elegant request.