In his “Letter to the Duke of Norfolk”, the next Doctor of the Church saint John Henry Newman understands conscience as a light that invites to obedience to the divine Voice that speaks in us and that the good exercise of this conscience consists in the fact of directing itself immediately to conduct, to something that must be done or not done. He also says that Jesus wanted the Gospel to be a recognized and authentic Revelation, public, fixed and permanent. Consequently, he constituted a society of people to be the guarantor of his Revelation. When he was about to leave the earth, he gave the Apostles the task of teaching those who were converted to keep all the things he had taught them. And He manifested to them that He would be with His followers until the end of the world and of history.

Newman adds that this promise of supernatural help did not expire with the disappearance of the Apostles, since Christ said “until the end of the world,” taking for granted that they would have successors and committing himself to be with those successors as he was with the Apostles. Revelation, Newman goes on to say, was given to the Twelve in its entirety and the Church only transmits it. He believes that the Church has the mission to teach faithfully the doctrine that the Apostles left us as an inheritance. By the teaching of the Church he understands not the teaching of this or that bishop but its unanimous voices and the Council is the form that the Church can adopt so that all recognize what she is teaching. In the same way, the Pope must present himself to us in a special way or with a special gesture, so that we understand that he is exercising his teaching office, that is, ex cathedra.

In his work on “The Development of Dogma” he affirms that the supremacy of conscience is the essence of natural religion and that supremacy in the conscience of the Christian is what is revealed to us in the New Testament and confirmed to us by the Church. He considers that the Catholic Church is the only one of all the Churches that dares to claim infallibility, as if a secret instinct and an involuntary suspicion restrained the other confessions.

In his book “Apologia pro vita sua” he says that he is compelled to speak of the infallibility of the Church as a disposition willed by the mercy of the Creator to preserve religion in the world and to restrain that freedom of thought - which is undoubtedly in itself one of our greatest natural gifts - in order to rescue it from its own self-destructive excesses.

In his book “Religious Assent” he states that he who believes in the depositum of Revelation, believes in all the doctrines of that depositum and, since he cannot know them all at once, he knows some doctrines and does not know others... but whether he knows little or much, he intends, if he truly believes in Revelation, to believe all that is to be believed whenever and as soon as it is presented to him.

He says that there is only one religion in the world that tends to satisfy the aspirations and prefigurations of natural faith and devotion, Christianity, and that it alone has a precise message addressed to all mankind.

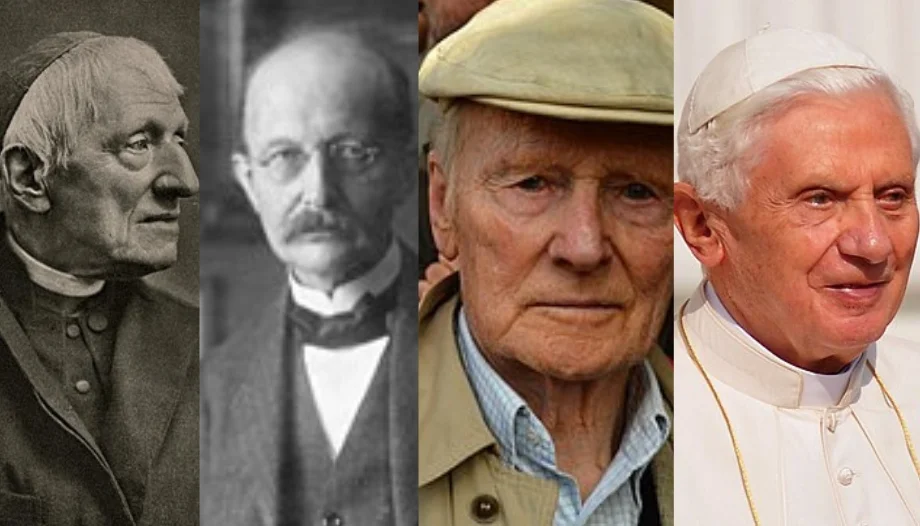

Plank, Spaemann and Ratzinger

For his part, the German Nobel Prize winner Max Plank, author of quantum theory, said in a conference: «Wherever we look, as far as we look, we do not find anywhere the slightest contradiction between religion and natural science, on the contrary, we find perfect agreement on the decisive points. Religion and natural science do not exclude each other, as some fear or believe today, but complete and condition each other. The most immediate proof of the compatibility of religion and the science of nature, also of that built on critical observation, is offered by the historical fact that precisely the greatest natural scientists of all times, Kepler, Newton, Lebnitz, were men penetrated by deep religiosity».

And that same lecture by Plank ended with the following words: «It is the ever-sustained, never flagging struggle which religion and natural science lead together against unbelief and superstition, and in which the slogan which marks the direction, which marked it in the past and will mark it in the future, says: Towards God!» (“Christ and the Religions of the Earth”, Franz Köning).

It is true that there are intelligent people dedicated to philosophy and science and unbelievers. But I prefer to remember, once again, someone who has been able to reconcile reason and faith: Robert Spaemann.

The German philosopher was once asked whether he, an internationally renowned scientist, really believed that Jesus was born of a virgin and worked miracles, that he rose from the dead and that, with him, one receives eternal life. Such a faith, they told him, is typically childish.

The 83-year-old philosopher replied: “Well, if you like, that's the way it is. By the way, I believe more or less the same as I did when I was a child, only that I have reflected on it more in the meantime. In the end, reflection has always confirmed me in the faith.”.

To this anecdote Benedict XVI added: «Why should God not be able to give birth to a virgin as well? Why should he not be able to resurrect Christ? Of course, if I myself establish what is allowed to be and what is not, if I and no one else determine the limits of what is possible, then such phenomena must be excluded... God wanted to enter this world. God wanted us not to be limited to sensing it only from afar through physics and mathematics. He wanted to show himself to us...» (“The Light of the World,” a conversation of Benedict XVI with journalist Peter Seewald).