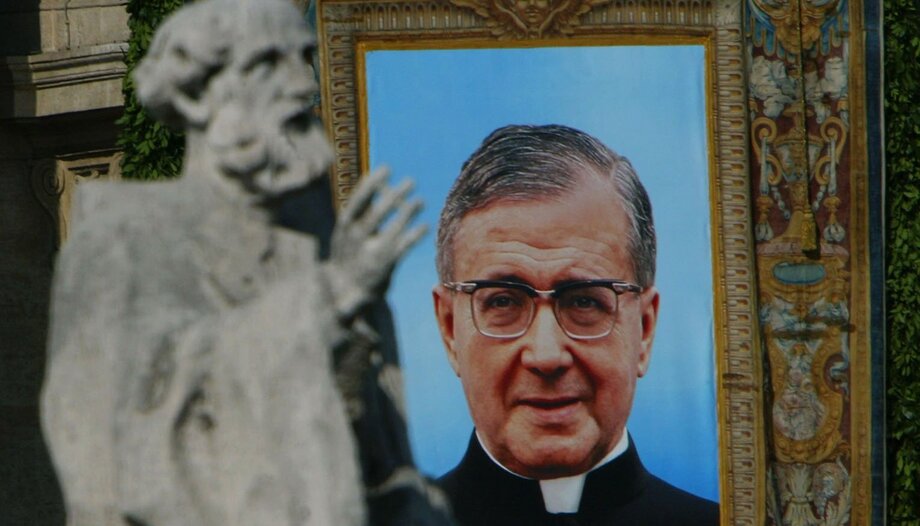

June 26, 2025 will mark the 50th anniversary of the death in Rome of St. Josemaria Escriva, founder of Opus Dei. This institution of the Catholic Church, which in 2028 celebrates its first centenary of existence, has often been surrounded by controversy, as the Church itself has been for more than 2000 years and as Jesus Christ himself and his apostles were from their beginnings in Jerusalem.

On October 2, 1928, St. Josemaría saw in Madrid that God was asking him for a new foundation in the Church with the charism of living with peaceful radicalism the baptismal vocation in the midst of the world (sanctifying work, the family and all good human realities) in order to be instruments of God and transform it from within. To this end, the cooperation of priests and lay people who lived a healthy anticlericalism was essential.

One of the problems of the Church, since its legalization by Emperor Constantine and subsequent declaration as the official religion of the Roman Empire by Theodosius, has been the temptation of Caesaropapism and clericalism, the latter so opportunely denounced by the last Popes.

St. Josemaría Escrivá and the laity

Together with a great love for the priesthood and consecrated life, St. Josemaría Escrivá understood that God was asking him to found an institution that would have as one of its essential features the secularity of its members, following Christ's famous maxim "give to Caesar what is Caesar's and to God what is God's"., precisely so that the Church could faithfully live its missionary vocation.

Perhaps it is this, together with the human errors involved in everything we men do, that has provoked so much antipathy against Escriva and Opus Dei since its inception on the part of the enemies of the Church (who are often more astute than the children of light in detecting who can be more dangerous in fighting evil) and on the part of some in the Church itself: their healthy anticlericalism.

The novel and scandalous for some "autonomy of temporal realities" proclaimed by the Second Vatican Council implies precisely, as I understand it, avoiding ecclesiastical politics and clerics falling into the temptation of bypassing civil and canon law, thinking that in a parish or diocese the pastor has absolute authority over what the lay faithful or laity do or do not do in their jobs, associations, in politics, the arts, etc. Each of us in the Church has our own mission. Perhaps the concept of synodality that is being used in recent years goes in this direction.

This message is reflected in many conciliar documents, as in Lumen Gentium, n. 33: "It belongs to the laity by their own vocation to seek the kingdom of God by dealing with and ordering, according to God, temporal affairs. They live in the world, that is, in each and every activity and profession, as well as in the ordinary conditions of family and social life with which their existence is interwoven. There they are called by God to fulfill their proper task, guided by the evangelical spirit, so that, like leaven, they may contribute from within to the sanctification of the world and thus discover Christ to others, shining forth, above all, by the witness of their life, faith, hope and charity.".

Love of freedom

Contrary to the caricature that some people try to maintain, the reality is that St. Josemaría tirelessly preached his love for freedom of opinion and, in particular, for religious freedom. He tended to take the side of the persecuted and abhorred the cessationist mentality, opposing those who elevated their opinion to dogma by trampling on others.

He did not like fundamentalism but coherence and asked not to confuse intransigence with intemperance (not to be a "hammer of heretics"). He knew how to distinguish the error of the person who is a fence-sitter and to give in to the opinionated in order to facilitate understanding and coexistence. He saw the danger of turning life into a crusade and seeing giants where there are only windmills, like the famous nobleman from La Mancha. A message that I see as very timely in these times of intransigent populism, of walls, repatriations and sanitary cordons against political options different from one's own.

He warned against pessimism because what is Christian is rather hope and optimism. He always encouraged the broadening of horizons and the deepening of the permanently living Catholic doctrine, following the successes of contemporary thought and avoiding its errors. All centuries have had good and bad things and ours is no exception. He encouraged a positive and open attitude towards the transformation of the world and social structures. He asked us to sow peace and joy everywhere, to be on the side of those who do not think as we do.

He saw good government as service to the common good of the earthly city and not as property. He encouraged Christians in politics not to live by politics alone, to share responsibilities, to surround themselves with valuable people and not with mediocre ones, to make decisions by listening to their collaborators. To not judge people and situations lightly without knowing, to learn from others, to elaborate fair laws that citizens could comply with, thinking especially of the weakest. Not to perpetuate oneself in power and to avoid right-wing and left-wing sectarianism.

Pursuits and courage

If Jesus and his followers have been persecuted from outside and from within the Church itself (in this case always with good intentions, as St. Josemaría used to say), the present era heralds good times for this charism, so necessary in the Church yesterday, today and always.

St. Josemaría Escrivá, with his defects, like all saints, was one of the greatest Spaniards in history (along with Isidro Labrador, Teresa of Jesus, Domingo de Guzmán, Ignatius of Loyola, Francis Xavier and so many others) and surely not the last. It seems to me that a proof of his greatness, which is of the God he let do within himself, is how little valued he has been so far in the field of worldly and ecclesiastical "triumphs".

The Aragonese priest who died in Rome half a century ago was a profoundly modern saint who never sought personal glory but rather to be faithful to the will of God and to serve the Church with his life and, if necessary, with his human honor. Now that we are accompanying with our prayer the first steps of Pope Leo XIV, with his courageous call to be good disciples of Christ in a world so in need of his light and to fearlessly proclaim the Gospel, we may find his teachings useful.