In the excellent biography written by Yuri Felshtinsky, it is stated that Orwell, who had traveled in 1937 to the Spanish Civil War under the pretext of studying the role of the Catholic Church in the war, found in his contact with anarchism and communism in Catalonia the source of his future rejection of the roots of totalitarianism and bureaucratic collectivism. About a conversation with an Anglican vicar who visited him, he stated with his characteristic irony that he had to admit that it was true "about the burning of churches, but that he was very happy to hear that they were only Catholic churches."

Anticommunism

In 1946, he published together with other authors in the Forward newspaper an open letter in which they asked that the Moscow trials of 1936-1938, in which the defendants (close collaborators of Lenin and Trostski) were held responsible for maintaining direct relations with the authorities of the Nazi Reich and the Gestapo; the German-Soviet friendship treaties; the murder of Polish civilians and soldiers in the Katyn forest at the hands of the Soviets, etc., be addressed in the Nuremberg trials. The letter had no repercussions because the British and American governments of the time were not interested in confronting the USSR.

Until the last day of his life, Orwell kept jotting down in a notebook an expanding list of individuals in the West who, in his opinion, were either underground communists or agents of Soviet influence. His anti-communist sentiments grew more acute during his last months of life, eventually sending a list of 36 people to an old acquaintance who worked in the Information Research Department, whose aim was to combat communist propaganda in the British Empire.

Final disease

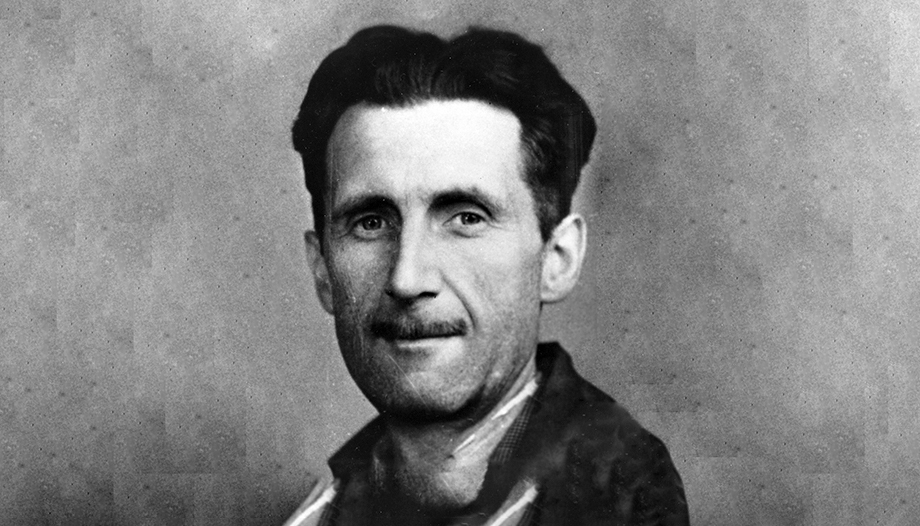

As D. J. Taylor wrote in an article in The GuardianEvery afternoon in January 1950, a small procession of visitors could be seen making their way, one by one, through the cheerful squares of North Bloomsbury to the University College London hospital where Eric Arthur Blair, known worldwide as George Orwell, was dying.

The British writer had been at UCH and in the hospital for almost four months since the beginning of the previous year. Two decades of chronic lung problems had resulted in a diagnosis of tuberculosis. In a Gloucestershire sanatorium six months earlier, he had nearly died, but recovered sufficiently to be transferred to London and cared for by the distinguished chest specialist Andrew Morland.

Fortunately, money, the absence of which had troubled Orwell for most of his adult life, was no longer an issue. 1984published the previous June, had been a great success on both sides of the Atlantic. Sixteen years younger than Orwell, with a string of previous mistresses, Sonia Brownell seemed an unlikely candidate for the role of second wife to the writer, widowed since the death of Eileen O'Shaughnessy in 1945. But the marriage was celebrated in the presence of the hospital chaplain, the Rev. WH Braine, in Orwell's room on October 13, 1949. Present were David Astor, Janetta Kee, Powell, a doctor and Malcolm Muggeridge, a left-wing writer friend of Orwell's who would eventually convert first to Christianity and almost at age 80 to Catholicism.

In the early hours of Saturday, January 21, Orwell died of a massive pulmonary hemorrhage. The news spread throughout the weekend. "G. Orwell is dead and Mrs. Orwell, presumably, is a wealthy widow." noted Evelyn Waugh in a letter to Nancy Mitford. Muggeridge, then working at the Daily Telegraph, wrote a couple of commemorative paragraphs for the Peterborough column. "I thought of him, as of Graham [Greene], that popular writers always express in an intense way some romantic longing....".

Will

The deceased turned out to have made a will three days before his death, in the presence of Sonia and his first wife's sister, Gwen O'Shaughnessy. Materially, he was transferring his literary estate to Sonia. A substantial life insurance policy would take care of his adopted son, Richard, who was then in the care of his aunt, Orwell's sister Avril. Orwell, who during his lifetime considered himself an agnostic, although he recognized the importance of Christianity to Western civilization, arranged for him to be buried according to the rites of the Church of England and for his body to be interred (not cremated) in the nearest cemetery. The task of arranging all this fell to Powell and Muggeridge.

Both friends attempted to engage the services of the Reverend Rose, vicar of Christ Church, Albany Street NWI. Astor's influence secured a plot in the graveyard of All Saints' Church, Sutton Courteney, Oxfordshire. Muggeridge noted in his diary the fact that Orwell died on Lenin's birthday and was buried by the Astors, "which seems to me to cover the whole range of his life."

Funeral

The funeral was set for Thursday, January 26. The evening before, Powell and his wife, visited the Muggeridge's after dinner, taking Sonia with them, "obviously in poor condition". At their last meeting, the day after Orwell's death, Sonia had been overcome with grief. Muggeridge decided that "I would always love her for her real tears....".

He left a detailed account of the next day's events: Fred Warburg greeting mourners at the door of the church, the cold atmosphere, the congregation "largely Jewish and almost entirely non-believer." who had difficulty following the Anglican liturgy. Powell chose the hymns: "All people that on earth do dwell," "Guide me, o thou great Redeemer," and "Ten thousand times ten thousand." "I do not remember why." Powell later wrote, "perhaps because Orwell himself had spoken of the hymn, or because he was, in his own way, a kind of saint, even if he was not one of shining robes."

Both Powell and Muggeridge found the occasion enormously distressing. Muggeridge, in particular, was deeply moved by Powell's chosen reading from the Book of Ecclesiastes: "Then the dust shall return to the earth as it was, and the spirit shall return to God who gave it." He returned to his home near Regent's Park to read the sheaf of obituaries written by, among others, Symons, VS Pritchett and Arthur Koestler, seeing in them already. "how the legend of a human being is created".