When Karol Wojtyła acceded to the See of Peter in October 1978, the whole world realized that a new era in the apostolic succession was beginning. Just as that young Pope developed a special rapport and complicity with representatives of art, culture, and communication, he also showed a clear affinity for the medium of film. His closest collaborators attest to this. For example, Cardinal Stanisław Dziwisz, his private secretary for forty years, said: “John Paul II loved cinema and watched the important films of the day.”.

For his part, the then Archbishop John P. Foley, who was president of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications for many years, attested that “the Holy Father knows cinema well and has been able to see films by directors from different countries.”.

Finally, Joaquín Navarro-Valls, spokesman for the Holy See during almost his entire pontificate, added: “St. John Paul II liked cinema and knew how to appreciate it, although he saw little of it. In any case, he liked to keep abreast of film production and asked about it, especially about films with historical, biographical, or purely aesthetic content. He particularly liked stories that exposed a universal human theme and proposed a non-trivial solution. He was not immune to aesthetics, but above all he was attracted to human content.”.

A pontificate worthy of the movies

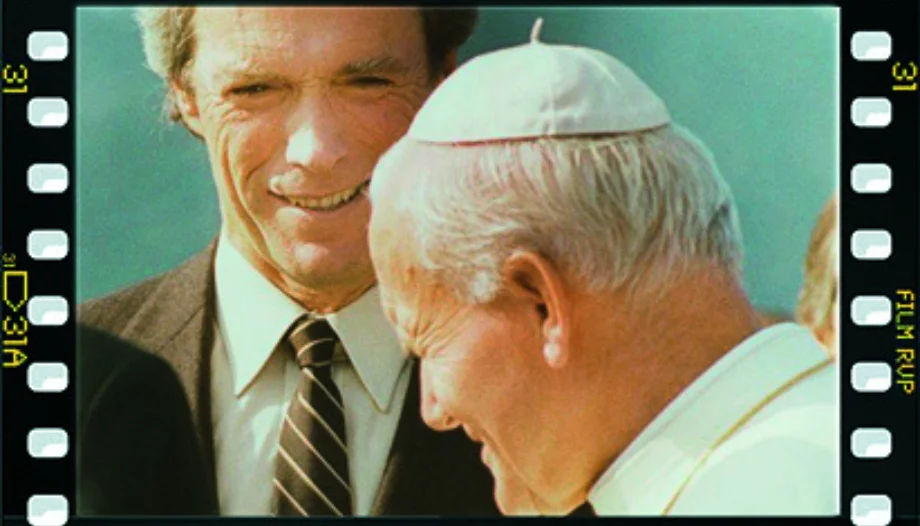

In one way or another, the world of cinema was very present during the pontificate of St. John Paul II. Indeed, during those years, there were numerous encounters with actors, filmmakers, and television professionals on the occasion of audiences, jubilees, or private screenings of films. Names such as Alberto Sordi, Vittorio Gassman, Monica Vitti, Dario Argento, Roberto Benignini, Andrei Tarkovsky, Krzysztof Zanussi, Ettore Bernabei, Ennio Morricone, Martin Sheen, and Jim Caviezel paraded through the Vatican chambers. The same was true of the producers of the series on the Bible, with whom the Pope met on several occasions. Among all these meetings, one that stands out is the one he held, on his own initiative, with a large representation of the Hollywood industry at the Beverly Hills Hotel Registry in September 1987, during his pastoral visit to the United States, which was attended by figures such as Lew Wasserman, Jack Valenti, and Charlton Heston.

Special mention should be made of the friendship between Saint John Paul II and his compatriot, Polish film director Krzysztof Zanussi, who directed the first biographical film about the life of the new pontiff: From a Far Country (From a distant country, 1981). The biopic by Zanussi was the first, but not the last, because, as George Weigel stated, Karol Wojtyła's own life story—both epic and dramatic—would “defy the imagination of even the most famous screenwriter.” Indeed, in 1984, the American television movie Pope John Paul II, directed by Herbert Wise and starring Albert Finney, and after Wojtyła's death in 2005, other television productions, demonstrating the interest his figure aroused.

In another context, it is worth mentioning the conferences and study days on the seventh art that were promoted during his years at the head of the Church—among which the three editions of the International Congress of Film Studies stand out, as well as the creation of a specific film festival called the Terzo Millenio Film Festival, whose first edition took place in 1991. Finally, it is worth adding another smaller festival, The John Paul II Inter-Faith Film Festival (JP2IFF), which emerged in 2009 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Letter to the Artists.

A brief but profound teaching

This extensive introduction serves as context for understanding why Saint John Paul II wanted to pay special attention to cinema and why he devoted a small but very substantial part of his teaching to it. Specifically, the core consists of just over a dozen speeches in which he refers to cinema and television fiction in a monographic manner and which took place between 1978 and 1999, that is, throughout almost his entire pontificate. Some of these speeches were given during meetings with professionals in the sector; others were given at conferences or congresses on cinema; and finally, there are those he dedicated to the seventh art on the occasion of its first centenary. Below is a summary of the most relevant ideas contained in all of them.

Cinema and human mystery

Like other arts, cinema, thanks to the evocative and emotive power of its language and the force of its dramatic representation of human life, contributes, in the words of Saint John Paul II, “to a better and deeper awareness of the human condition, of the splendor and misery of man.” Hence, he insisted: “Cinema is, therefore, a highly sensitive instrument, capable of reading in time the signs that sometimes escape the gaze of a hasty observer. When used well, it can contribute to the growth of true humanism and, ultimately, to the praise that rises from creation to the Creator.”.

It is precisely in the richness of the cinematic medium—images and sounds at the service of a story—that this connection with the viewer is achieved, allowing them to vicariously experience the lives of others in a drama laden with meaning (the cathartic experience alluded to by the Greeks). Thus, this holy Pope explained: “Cinema enjoys a wealth of languages, a multiplicity of styles, and a truly great variety of narrative forms: realism, fable, history, science fiction, adventure, tragedy, comedy, chronicle, cartoons, documentaries... Therefore, it offers an incomparable treasure trove of expressive means to represent the various fields in which human beings are situated, and to interpret their essential vocation to beauty, the universal, and the absolute.” As can be seen, for this Roman Pontiff, cinema, being an ideal vehicle for expressing the transcendent dimension of man, possesses a unique performative and salvific quality, characteristic of all cultural manifestations based on an adequate anthropology, characteristic of those artistic expressions that open themselves to the spirit and show the intimate relationship that exists between beauty, truth, and goodness. Hence, he adds: “When watching films, viewers are prompted to reflect on aspects of a reality that is sometimes unknown to them, and their hearts are questioned, reflected in the images, confronted with different perspectives, and cannot remain indifferent to the message that the film conveys.”.

Cinema as an individual and social educator

On several occasions, Pope Wojtyła uses the term pedagogue o cultural agent, to reinforce the idea that all screens, large and small, have become instances that shape the values that concern individual and social consciousness, supplanting the family, school, and religious education. He once pointed out: “Among the social media, cinema is undoubtedly a widely used and appreciated instrument, and it often sends out messages capable of influencing and conditioning the choices of the public—especially the youngest—as a form of communication based not so much on words as on concrete facts, expressed with images that have a great impact on viewers and their subconscious,” to the point that “through the models of life they present, with the suggestive effectiveness of images, words, and sounds, the media tend to replace the family in the role of preparing for the perception and assimilation of existential values.” Cinema thus becomes a mirror and model of society, and an agent of social cohesion and cultural exchange. Specifically, to the representatives of Hollywood, the main entertainment production and export machine, I pointed out on the occasion of a meeting in 1987: “You help your fellow citizens enjoy leisure, appreciate art, and benefit from culture. You often provide the stories they tell and the songs they sing. You supply them with news about daily events, a vision of humanity, and reasons for hope. Your influence on society is certainly profound. Hundreds of millions of people watch your movies and television programs, listen to your voices, sing your songs, and reflect your opinions. It is a fact that your smallest decisions can have a global impact.”.

Social responsibility of professionals

It is not surprising that, faced with such power, Saint John Paul II demanded a corresponding responsibility. He did so on many occasions, most notably in his speech to the Hollywood film industry. “My visit to Los Angeles would be incomplete without this meeting, because you represent one of the most important factors influencing the United States in today's world. You work in all fields of social communications and thus contribute to the development of a popular mass culture. Humanity is deeply influenced by what you do. Your activities affect communication itself.: providing information, influencing public opinion, offering entertainment (...). You often provide the stories they tell and the songs they sing. You supply them with news about everyday events, a vision of humanity, and reasons for hope. Your influence on society is certainly profound.” He added: “Your work can be a force for great good or great evil. You yourselves know the dangers and the splendid opportunities that lie before you. Communication products can be works of great beauty, revealing what is noble and uplifting in humanity, and promoting what is just, equitable, and true. On the other hand, communication can appeal to and promote what is degrading in people: dehumanized sex through pornography or through a superficial attitude toward sex and human life; greed through materialism and consumerism or irresponsible individualism; anger and revenge through violence or vigilante justice. All the means of popular culture that you represent can build or destroy, elevate or debase. You have incalculable possibilities for good and abominable possibilities for destruction. It is the difference between death and life—the death or life of the spirit. And it is a matter of choice.

Among the most pressing challenges that this Pope points out in his speeches are respect for the viewer—based on human dignity—the transmission of positive values in defense of true humanism, the responsible representation of controversial topics such as violence or sex, the promotion of a true common good, the defense of creative and responsible freedom, and resistance to commercial and ideological interests.

Ultimately, it is a question of film and audiovisual media professionals responding to the trust that the community places in them. In this regard, the saintly Pope concluded: “Certainly, your profession subjects you a high degree of accountability –before God, before the community, and before the witness of history. And yet, sometimes it seems that everything is left in your hands. Precisely because your responsibility is so great and your accountability to the community is not easily enforceable from a legal standpoint, society relies so heavily on your goodwill. In a sense, the world is at your mercy. Errors of judgment, mistakes about the appropriateness and justice of what is transmitted, as well as erroneous criteria in art can offend and hurt consciences and human dignity. They can usurp sacred fundamental rights. The trust that the community places in you It deeply honors you and powerfully challenges you.".

Responsibility of the viewer

However, the sense of responsibility is not limited to professionals. It is a shared responsibility that also involves those who enjoy audiovisual content, i.e., viewers. It is up to them to develop their critical skills to correctly interpret the messages they receive through the small or big screen, and thus be in a position to make free and responsible use of such audiovisual content. Similarly, this includes parents and educators, in the case of minors, as well as the role of film critics.

The principles underpinning this duty to educate (or be educated) in the use of the media are rooted in an anthropological vision that defends human dignity and free and responsible action. It is no coincidence that Saint John Paul II insisted on this from the beginning of his pontificate. For example, in 1981 he recalled: “Man, also in relation to the mass media, is called to be ‘himself’: that is, free and responsible, a ‘user’ and not an ‘object’, ‘critical’ and not ‘passive’ (...). This is the dignity that requires man to act according to conscious and free choices, that is, moved and induced by personal convictions and not by a blind internal impulse or mere external coercion.” And further on, he continued: “Direct action must be intensified to form a critical conscience that influences the attitudes and behaviors not only of Catholics or Christian brothers and sisters—defenders by conviction or by mission of the freedom and dignity of the human person—but of all men and women, adults and young people, so that they may truly know how to ‘see, judge, and act’ as free and responsible persons, including in the production of and decisions regarding the media.”.

Specifically, this Pope proposed promoting critical education in cinema and the audiovisual arts, especially in the case of children and adolescents (who are most vulnerable to messages conveyed on screens); the responsibility of parents and educators; and, finally, the role of film critics, who have the mission of helping to shape viewers' critical awareness.

Cinema, a vehicle for evangelization

It is quite logical that someone who understands so deeply the nature of cinema and its ability to penetrate the human soul would think of it as a means of transmitting the contents of the faith. “Cinema, with its many possibilities, can become a valuable tool for evangelization,” he once said. The Church urges directors, filmmakers, and all those who—at any other level—profess to be Christians and work in the complex and heterogeneous world of cinema to act in a manner fully consistent with their faith, courageously taking initiatives even in the field of production to make the Christian message, which is a message of salvation for all people, increasingly present in that world through their professional work.“ Specifically, the stories reflected on the screen can help to bridge the gap between faith and culture. Thus, he invited a group of professionals: ”I trust that your film productions will be a valuable aid to the indispensable dialogue that is developing in our time between culture and faith. In a special way, in the field of film and television, where history, art, and the languages of communication meet, your work as professionals and believers is particularly useful and necessary.".

A perennial invitation

Karol Wojtyła was a pope who showed particular sensitivity toward the medium of film. He understood it deeply in all its dimensions: as art, as industry, and as a means of communication. This is a unique case in recent pontificates. His teaching will remain a source of inspiration. This was recognized by the then president of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications, Archbishop Foley: “The Holy Father's messages on cinema can be considered a starting point for reflection and remind us once again how much attention John Paul II has paid to the big screen. It is a call to responsibility, an encouragement to continue along the path that many have taken, especially in light of an indispensable consideration: that cinema is an integral part of a people's culture, representing their desires, fears, and hopes, and that each film remains a testament to this culture, speaking to future generations and bringing forgotten or unknown moments back to mind.” Indeed, this brief but profound teaching will continue to enlighten those who work in the audiovisual industry, with the desire—in the words of St. John Paul II himself—that “the film industry throughout the world reflect on its potential and assume its important responsibility.”.

Saint John Paul II and Cinema Truth, goodness, and beauty on screen

Priest. Doctor in Audiovisual Communication and Moral Theology. Professor of the Core Curriculum Institute of the University of Navarra.