Rome is a city that never ceases to be discovered and never ceases to amaze. Its records are innumerable: city with the longest inhabited continuity in Europe (along with Matera, also in Italy); capital of the Roman Empire, of Christianity and of the Italian Republic; city with the largest number of UNESCO properties in its hinterland; city with the most churches in the world (over 900, including the largest church in the world, St. Peter's), with the largest amphitheater of antiquity (the Colosseum) and the most advanced hydraulic system of the ancient world (to which the imposing aqueducts bear witness), but also with the oldest (and still standing: the Pantheon). And many other firsts.

For these reasons it is known as the Eternal City. However, for those who want to go beyond the records and the best-known monuments, Rome has a hidden heart and a thousand surprises. Among them, the basilica and catacombs of St. Sebastian, on the ancient Appian Way, the first Roman consular road (312-244 BC), known as "regina viarum", which connected the capital to the Adriatic port of Brindisi. Here, where taverns and a handful of dwellings once stood, a necropolis developed from the second century A.D. on top of which a basilica complex was built.

From necropolis to cemetery: the Christian invention

In pagan times, according to Greek, but also Etruscan and Roman custom, the places destined for the burial of the deceased were not called cemeteries, as we know them today, but necropolis (from the Greek "νεκρόπολις", "nekrópolis", a term composed of "νεκρός", "nekrós", i.e. "dead", and "πόλις", "pólis", "city").

The deceased were not buried, but in most cases were cremated and their ashes were kept in urns placed in niches. The wealthiest families had, as today, private chapels and, when visiting the catacombs of St. Sebastian, it can be seen how these were sometimes also equipped with roofs with a small terrace for the "refrigerium", the refreshment in honor of the deceased relatives.

The change from necropolis to cemetery was not a simple change of term, but a revolution in the way of conceiving death, which, in the Christian era, was no longer the natural end of this life, but the beginning of another, even more real, in which the body would also participate. Therefore, it began to bury the dead, who, according to Christian doctrine, are considered "asleep" awaiting the resurrection (both in San Sebastiano and in other catacombs and in the necropolis under the Basilica of St. Peter can be observed "mixed" tombs, perhaps of the same family, with niches in which the urns with the ashes of the pagans were kept next to larger niches to house the complete body, unburned, of a Christian deceased.

The term itself, "cemetery" (from the Greek "κοιμητήριον", "koimētḗrion", "dormitory", whose root is the verb "κοιμάομαι", "koimáomai", "to sleep") thus came to designate a place of rest, not death.

Christian cemeteries were built next to churches (or under them) until the Edict of Saint-Cloud (1804), when Napoleon Bonaparte imposed, for hygienic reasons, the burial of the dead outside urban centers (lovers of Italian literature will remember, in this regard, the beautiful poem "I sepolcri" (The Tombs), by Ugo Foscolo, inspired by this event).

To the catacombs

The word "catacomb" derives from the Latin "catacombs" (although of Greek origin), which means "cavity", precisely to indicate the natural conformation of the terrain in this area of Rome, where there were ancient pozzolana quarries (descending from the Appian Way), and by extension became synonymous with subway necropolis. In this place, from the 2nd century onwards, an immense funerary area developed (about 15 hectares, i.e. 150,000 m² of subway galleries, at least 12 km of tunnels and corridors and thousands of tombs, rich in inscriptions and graffiti in Latin or Greek, Christian symbols such as the dove, the fish, the anchor and numerous paintings, more than 400, many of them still beautifully preserved), first pagan and then also Christian.

According to a consolidated tradition, the bodies of St. Peter and St. Paul were temporarily deposited in these same catacombs during the first persecutions, to be later transferred respectively to the Vatican and to St. Paul Outside the Walls. This would be compatible with the finding, in the necropolis located under St. Peter and near the bones attributed to the Prince of the Apostles, of a wall with an opening that seems to indicate a removal and subsequent relocation of the same bones.

In one of the most evocative rooms of the catacombs of St. Sebastian, called Triclia, there are numerous graffiti engraved by the ancient pilgrims, such as: "Petre, Pauli, in mente habete nos", "Peter and Paul, remember us".

In fact, the place became the destination of numerous pilgrimages, especially after the martyrdom of St. Sebastian, a Roman officer converted to Christianity and executed under Diocletian (around 288 A.D.), buried here by a Christian matron, Lucina, who found his body thrown into the Cloaca Maxima.

The basilica and the "Salvator Mundi".

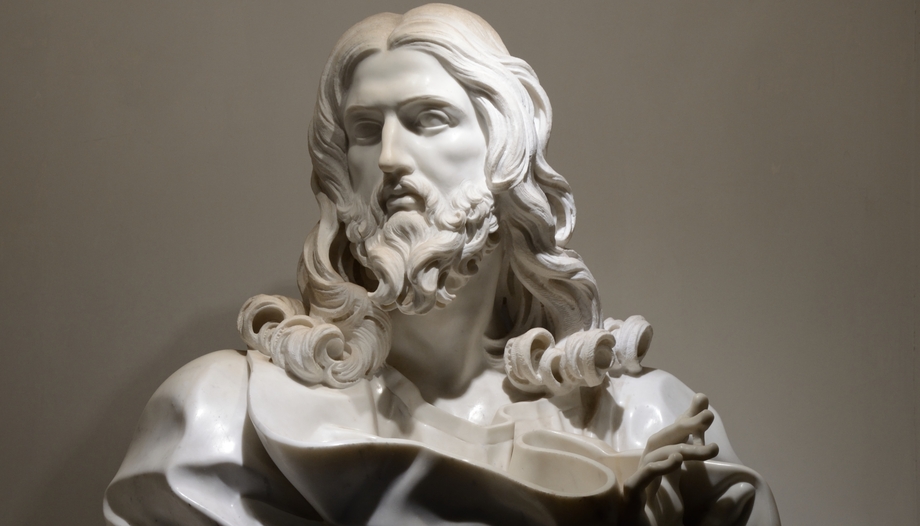

The basilica was originally built in the 4th century by order of Emperor Constantine, right on the place where St. Sebastian was buried, "ad catacombas" ("next to the cavities"). Today, its appearance is the result of numerous subsequent interventions, in particular the 17th century restoration commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese. The most famous works inside are undoubtedly the chapel that guards the relics of Sebastian, above the high altar, and the statue of the saint, made by Bernini. Also by the great master is another magnificent work, the "Salvator Mundi", his last work, probably made more out of personal devotion than by commission, and which was donated by Bernini himself to the basilica. Its trace was lost until 2001, when it was found by chance and put back on display.

Curiously, precisely in San Sebastian is one of the first representations of Christ the Savior of the world (represented here for the first time as a real and cosmic figure and no longer only as a good shepherd and teacher). It is part of the pictorial heritage of the more than 400 works found in the catacombs (in this case, after a detachment in 1997). It dates from the late third and early fourth century, and represents Christ facing the front in an attitude of blessing, with a scroll (volume) in his right hand and two people behind him (perhaps Peter and Paul).

San Felipe Neri and the Path of the Seven Churches

In the Middle Ages, the Basilica of St. Sebastian was already one of the "Seven Churches" most visited by pilgrims to Rome. However, it was St. Philip Neri who institutionalized this urban pilgrimage as an alternative both to the more important pilgrimages (such as that to Santiago de Compostela) and to the revelries of the Roman carnival (proposing it above all to young people as a penitential activity, but not too much, according to his unmistakable style).

The route continues today along the main places of faith in Rome (the major basilicas linked to the most important martyrs and saints) and makes a stop in San Sebastiano, where, among the catacombs, there is also the chapel where St. Philip Neri prayed without ceasing and, according to tradition, was the protagonist of a mystical event, the famous "dilation of the heart".

I have been to San Sebastian many times, I have been spellbound by the statue of Bernini's "Salvator Mundi", I have walked through tunnels and galleries frescoed and graffitied by thousands of pilgrims over two thousand years of history, imagining a family in ancient Rome celebrating a banquet, or rather, a "refrigerium" (from which in Italian we have taken the term "rinfresco") in memory of their deceased.

However, it was during the night pilgrimage through the Seven Churches, in the mystical silence that envelops the basilica and the nearby catacombs, that I felt closer to the heart of Rome and the heart of man, "in the cold and black earth", as the great poet Carducci would say, but with the hope that, after death, the sun still cheers us and awakens our love.