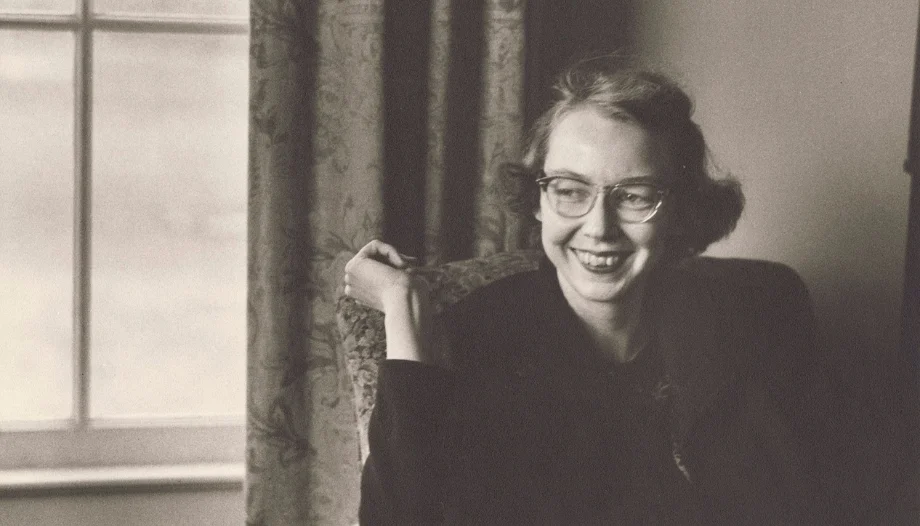

After the articles on Maria Callas y Whitney Houston I could not fail to write about another great woman and artist, Flannery O'Connor (1925-1964), one of the most original voices of twentieth-century American fiction. Her life lasted only forty years, but she left two novels and several short stories that changed the way of understanding the relationship between faith and literature.

As a narrator, I was struck by one of his phrases, typical of his style: "The idea of being a writer attracts many unfinished ones..." ("El vicio de vivir. Cartas 1948-1964"). For O'Connor, in fact, writing and art are not a narcissistic exercise, but a mission: to penetrate a "territory largely possessed by the devil" and try to tell the hidden presence of Grace (salvation, redemption).

Inspiration from the deep south

Flannery O'Connor was born in Savannah, Georgia, and lived most of her life in the deep rural south of the United States, marked by segregation and religious bigotry. She felt she was a "stranger in her own country" for being a Catholic in a Protestant environment. Afflicted by lupus, a disease that led to her death, she wrote much of her work on the family farm, "Andalusia", in Milledgeville.

Illness and isolation did not undermine his lucidity; on the contrary, they sharpened his vision, imbued with the certainty that Grace is never tameable.

In fact, his stories are populated by arrogant, racist, superficial, or religiously fanatical characters. Yet, at unexpected moments, Grace literally bursts into the lives of these same characters: not as a faint light from heaven or a "Deus ex machina," but as a harsh, sometimes brutal Grace that does not spare suffering.

In "A Good Man Is Hard to Find", the grandmother, intolerant and superficial, at the moment of her death feels an instant of genuine compassion for a criminal, to whom she says: "You are one of my sons". And this is the focus of O'Connor's narrative theology: the Grace that manifests itself precisely when illusions collapse.

O'Connor writes in a 1955 letter ("The Vice of Living"), "I believe that what is called religious experience is not something that can be hung as a label on a work, but must be in the very flesh of the story."

Art for art's sake

Art is often spoken of as oscillating between two extremes: on the one hand, pure form ("art for art's sake") and, on the other, art as a social or political instrument. O'Connor places herself between these two conceptions. In "The Devil's Territory" he writes: "Narrative should never be used as a vehicle for abstract ideas". In fact, "the task of the Christian storyteller is to show the mystery through the matter, not to eliminate the matter in order to get at the mystery."

On the one hand, therefore, he rejects the reduction of narrative to religious or political propaganda; on the other, he does not accept an aesthetic devoid of spiritual content.

As I wrote in other party As O'Connor is a radical witness, art cannot be only "useful", but neither can it be confined in an ivory tower. Authenticity is born of the tension between gratuitousness and responsibility.

To express this tension, O'Connor chooses an instrument: the "grotesque". The term, which derives from the "caves" of the Domus Aurea of Nero The paintings, in which paintings depicting fantastic and extravagant characters were found, indicate what is both comical and disturbing at the same time and recall, in Italian literature, the style of Luigi Pirandello.

Deformed figures, sudden violence, comic or cruel scenes: O'Connor, in her writings, makes the reader see reality without veils, since deformity and excess are precisely ways through which, in her literature, Grace can manifest itself. Today we would call them "existential peripheries".

For example, in "Wisdom in the Blood," the protagonist, Hazel Motes, founds a "Church of Christ without Christ," a tragic attempt to expel the religious from life, but his curious nemesis will testify to the inevitability of Grace.

The American "tradition

Flannery O'Connor is part of a long line of American storytellers who delve into the conscience of the country, such as Faulkner and McCullers, but she is distinguished by her theological vision that does not fear the "scandal" of Grace. His harsh language and radical vision do not "comfort" the reader, but reveal the Christian mystery.

As I read it, I thought I saw some traits of the writing of Raymond Carver, master of minimalism. Like O'Connor, Carver does not speak of heroes or extraordinary characters, but of mediocre people, often defeated by life, "without appearance or beauty".

The two authors also share an obsessive attention to the everyday, which translates into a concept that is very dear to me: the "eyes" and memory, to observe, remember and capture in the narrative events and physical and psychological characteristics of real people. Eyes and memory are, therefore, as necessary a component for the storyteller as talent and the gift of contemplation.

Carver leaves his protagonists suspended, without redemption or transcendental openings. O'Connor, on the other hand, shows the same human misery, but seasoned with a generous dose of Grace: not an insignificant salvation, but the possibility of redemption.

A figure more current than ever

In the current cultural debate in the United States, antithetical and polarizing figures emerge: "the woke" on the one hand, extremist conservatives (evangelicals, but not only) on the other, who use the media to assert an identitarian and militant vision. This leads us to reflect on the different Catholic vision, compared to the Protestant one, on communication and presence in the public sphere.

The Second Vatican Council, with "Inter mirifica" and subsequent documents, but also with "Gaudium et Spes" and John Paul II's Letter to Artists, indicated to communicators and artists a style based on sobriety, respect and dialogue. However, certain communicative models very much in vogue today privilege sensationalism, visibility at any price and the search for followers, with an often aggressive and divisive style that feeds fundamentalism and spectacularization.

Flannery O'Connor was quite the opposite: from her farm in Georgia, she rejected propaganda and warned against the instrumental use of narrative and art for social or political purposes. The risk, from his point of view, was the transformation of Christianity into slogans, depriving it of the "scandalous" and mysterious dimension of Grace. And this is not only a communicative risk, but a purely theological one.

It is not a question here of an absence of redemption (as in Carver), but of a blatant and conditional redemption, too materialistic, presented by the so-called "prosperity theology": the Gospel transformed into an instrument to guarantee success and earthly well-being, to the point of "reducing God to a power at our service, and the Church to a supermarket of faith"A "different gospel" that denies the scandal of the cross and of Grace.

Flannery O'Connor represents its antithesis: her characters do not obtain prosperity or success, but are overwhelmed, precisely in their existential peripheries, by a Grace that strips, humiliates and saves in an unexpected and unthinkable way.

Another area in which O'Connor embodies a typically Catholic vision is that of "identity". Unlike Protestant fundamentalism, where faith and politics are closely linked, Catholicism has developed over time (especially thanks to Benedict XVI) the concept of "positive secularism": neither state religion nor private faith, but leaven in society (as in the Letter to Diognetus).

Flannery O'Connor, with her life and her art, does not make propaganda and remains a complex figure, able, with a writing often ruthless, to show without reservation the existence and the seriousness of evil, but also the scandal of a Grace able to venture, without being reduced to ideology, in the "territory of the devil".